Environment

Sources: The Active Tick Surveillance Program (ATSP)

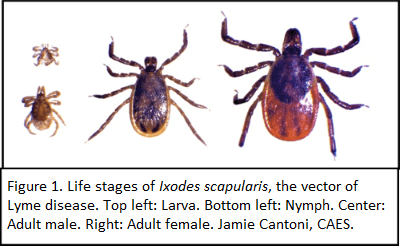

The Active Tick Surveillance Program (ATSP) has been a public health service in Connecticut since its establishment in the Spring of 2019. With an estimated 476,000 Lyme disease cases (spread by the black-legged, or deer tick, Figure 1)

The lone star tick, mostly native to the Southeast portion of the United States, was first discovered in 2017. It was found in Fairfield and New London counties in 2019. The tick, while not a carrier of Lyme disease, is known for its unusual ability to make some people develop a red meat allergy. Alpha-gal syndrome, also known as mammalian meat allergy, is a tick-borne allergy to a sugar molecule called alpha-gal, triggering delayed reactions to ingesting red meat. The surveillance effort allows Station scientists to be proactive in their attempts to monitor shifts in presence, abundance, and distribution of native and invasive tick species, and their associated risk for potential novel pathogen and disease transmission.

Since implementing the active surveillance program, new detections of the lone star tick (Amblyomma americanum), a species indigenous to the southern U.S., have occurred in Fairfield, Middlesex, New Haven, New London, and Windham Counties. Detections of the exotic long-horned tick (Haemaphysalis longicornis) have been confirmed in Fairfield, Middlesex, New Haven, and New London Counties (Figure 3).

Lone Star tick (Amblyomma americanum)

“The lone star tick doesn’t carry a ton of different pathogens, but there is concern about the alpha-gal syndrome,” said Megan Linske, an entomologist who specializes in ticks and tick-borne pathogens with CAES (Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station). “Another concern is the fact that where they tend to establish, they really take over the area. So we are monitoring them and how they progress over time.”

Figure 3. Map highlighting towns where new and invasive species of ticks have been identified since 2019.

Linske said the data didn’t show anything out of the ordinary from previous years, except that tick populations seem to be rising in Connecticut. “Tick ecology is a complex web, so there’s no one reason,” Linske said. “But several studies have shown that more mild winters have allowed ticks to better adapt and survive in the state. So we’re seeing more ticks being able to survive the overwintering process which is allowing more exotic ticks the ability to survive in greater numbers than previous years.”

“The key thing is to find the ticks early,” Linske said. “It takes about 24 to 48 hours for that pathogen to be passed from the tick to the host species, which would be a human. So if the tick is not fully engorged, you are probably OK. But it’s important to monitor the area of the bite and see a doctor immediately if you are experiencing any symptoms.”