Celebrate the Black Men and Women Who Made History.

Black History Month February 1st to March 1st

Source: The Archive

All Photos by Wikipedia Commons

- Rebecca Lee Crumpler was the first Black woman to become a doctor of medicine in the United States.

After moving to Charlestown, Massachusetts in 1852, Rebecca Crumpler worked as a nurse for eight years. At that time, the lack of official schools of nursing meant she required no formal training for the job. However, she certainly wasn’t afraid of some hard work. She was admitted into the New England Female Medical College in 1860 and graduated four years later with her M.D.

After the end of the Civil War in 1865, Dr. Crumpler moved to Richmond, Virginia, to provide medical care for the freed slaves who would otherwise have no one else to turn to. She dedicated herself to the understanding of diseases that particularly afflicted women and children, and when she eventually returned to Massachusetts, she opened her own clinic in Boston. She saw poverty stricken patients and treated them regardless of their ability to pay her.

- The Sugarhill Gang’s “Rapper’s Delight” became the first commercially successful rap record.

Photo Credit: Alchetron

Billboard has called Sylvia Robinson “Hip-Hop’s First Godmother,” but she still never seems to get the credit she deserves for cultivating the genre of rap. In the summer of 1979, Robinson conceived and produced the single “Rapper’s Delight.” This took a culture of music that thrived on the street and helped to foster it into an art form that was suddenly commercially viable. The song became the first rap single to dominate the radio and the charts, hitting number 36 on Billboard’s Hot 100 and becoming the first rap record to sell over one million copies.

- The practice of vaccinations was brought to America by a slave.

With the recent devastating spread of Covid and the life-saving vaccines that have started to turn the tide, some appreciation should be given to the man who brought this game-changing practice to the United States.

In 1721, a smallpox epidemic struck the city of Boston. This highly contagious virus was killing hundreds during a time of lesser medical advancements, and it was an enslaved man by the name of Onesimus that changed everything.

Onesimus was purchased in 1706 for Cotton Mather, a prominent Puritan minister. Though Mather held a great distrust for Onesimus, he knew that the man was clever. Amid the spreading sickness, Onesimus confided to Mather about the practice of inoculations, which had been used in Africa for centuries. Mather brought this vital information to Dr. Zabdiel Boylston, who, despite a major pushback against the idea, managed to successfully inoculate 240 people.

- The Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, which changed the perception of American dance, was founded in 1958.

Alvin Ailey was a dancer, director, choreographer, and activist who breathed life into one of the most prominent dance companies across the globe, the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater.

He also created the affiliated Ailey School, which not only served as a haven for up-and-coming Black artists, but showcased the universality of the African-American experience through dance. Bringing together ballet, jazz, modern dance, and theater, Ailey’s hopeful choreography was performed across the world, spreading awareness of Black life in America. Though he passed away in 2014, Ailey was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom for his groundbreaking work in bringing the expressive art of dance to underserved communities.

- Bayard Rustin, an LGBTQ rights activist, orchestrated the Civil Rights Movement from behind the scenes.

Born in 1912, Bayard Rustin was an openly gay Black man who acted as a key adviser to Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. In fact, he educated King on nonviolent civil resistance tactics, which he learned from a trip to India in 1948.

Rustin himself was instrumental in the organization of the March on Washington. Unfortunately, due to the criticism over his sexuality, Rustin was typically kept out of the spotlight and utilized only as an engineer of change in positions where he was not widely visible to the public.

Rustin was a humanitarian until his death in 1987, including a shift in focus to gay rights activism in the 80s. Like others on this list, he was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2013. In 2020, California Governor Gavin Newsom pardoned Rustin’s 1953 arrest, which stemmed from the criminalization of homosexuality.

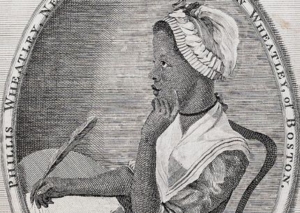

- Phillis Wheatley was only 12 when she became the first female African American author published.

Despite Phyllis Wheatley’s fame, we know surprisingly little about her early life. She was taken from her home in Africa when she was seven or eight, and sold to the Wheatley family in Boston. The family taught her to read and write, and encouraged her to write poetry as soon as they witnessed her talent for it. In 1773, Phyllis published her first poem, making her the first African American to be published. She was only 12 at the time.

Her work was praised by high-ranking members of society, including, perhaps most notably, George Washington. Her writing made her famous throughout the colonies. Not long after her poems were first published, the family that owned Wheatley emancipated her. Unfortunately, her life took a turn from there, especially after the deaths of many of the Wheatleys who had helped support her. She was stricken with poverty. The fame she earned from her writing did little to sustain her husband and children. She fell ill and died at the age of 31.

- MLK improvised the most iconic part of his “I Have a Dream” speech.

This fact may be the most surprising you’ll find here. When King was originally drafting his speech, the “dream” language was considered but ultimately edited out. He was only allotted five minutes to speak, and he didn’t think he’d have enough time to fit those words. When he handed the speech into the press, the words “I have a dream” were not included.

When they arrived at the march that morning, King was disappointed at the numbers the media was reporting—only about 25,000 had showed to protest. But by the time they reached the Lincoln Memorial, the numbers had swelled. Maybe this is what inspired King to suddenly change his speech. Whatever the reason, King’s improvisation made history.

- Hattie McDaniel, the first African American to win an Oscar, wasn’t allowed to attend Gone With the Wind‘s national premiere.

Hattie McDaniel was able to carve out a place for herself in Hollywood despite rampant racism and a consignment to bit parts. She paved the way for many African American women, but not without her fair share of obstacles. Her performance as “Mammy” in Gone With the Wind (1939) won her Best Supporting Actress at the Oscars that year.

However, the national movie premiere was in Atlanta. Because of Georgia’s Jim Crow Laws, she was prohibited from attending the event. Hattie went on to star in over 300 films, was inducted into the Black Filmmakers Hall of Fame in 2006, and was the first Oscar winner to appear on a postage stamp.

Despite her ultimate success, her choices (insofar as she had any) in roles were often criticized. The NAACP said Hollywood’s roles for African Americans were narrowed to servants or characters whose main purpose was being comically slow and dim-witted. Hattie was criticized for settling for lesser roles than her white colleagues. Despite this, Hattie went on to have a stellar career.

- Josephine Baker was a spy for the French during WWII.

Josephine Baker, one of showbiz’s most iconic performers, left the United States due to the overt racism she encountered in 1937. After marrying a Frenchman, Jean Lion, she moved to Paris and renounced her U.S. citizenship. In 1940, when the Nazis began their occupation of Paris, Baker showed just how deep her loyalty to her adopted nation was, becoming a spy for the Allies. During her travels across Europe to perform, Baker would conceal messages within her costumes or her sheet music for other Allied spies. She also used her status as a desired society presence to eavesdrop at various embassy events and balls.

- The ban on interracial marriage in the U.S. was overturned because of one couple in 1967.

Mildred and Richard Loving left their home state of Virginia to get married. They were warned by Virginia state officials that getting married would be a violation of state law, as Richard was white and Mildred was not. When they returned home, Mildred was promptly arrested. When she was finally released, the couple was referred to the American Civil Liberties Union by Robert Kennedy. The ACLU, seeing an opportunity to end anti-miscegenation laws, jumped at the chance.

After making their way through local and state courts, Loving v Virginia was put before the Supreme Court, and the bans on interracial marriage were deemed unconstitutional. It was a landmark victory for couples of different races, and the Lovings are often heralded as being the catalysts for making it happen. The last law formally prohibiting interracial marriage was overturned in Alabama in 2000. The Lovings were featured in a 2016 biopic, Loving, starring Ruth Negga and Joel Edgerton.

- Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated on Maya Angelou’s 40th birthday.

It may not be entirely surprising that Martin Luther King Jr. and Maya Angelou became friends during the Civil Rights era. Two prominent voices in the Civil Rights Movement, their paths crossed when Angelou was the coordinator for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and King paid the group a visit. In one of her autobiographies, she recalls MLK being shorter and younger than she expected but also said that he was friendly and constantly cracking jokes.

When King died on Angelou’s birthday, the writer was devastated. She stopped celebrating her birthday for many years following his death and sent flowers to King’s widow, Coretta Scott King, for more than 30 years, until Coretta died in 2006.

- Nine months before Rosa Parks, there was a young woman named Claudette Colvin.

On December 1, 1955, Rosa Parks refused to relinquish her seat on a public bus. Parks’ protest sparked the Montgomery bus protests and galvanized the Civil Rights Movement. Yet she was not the first African American individual in Montgomery to stand up against injustice in such a manner.

On March 2, 1955, fifteen-year-old Claudette Colvin was riding home on a city bus after a long day at school. A white passenger boarded, and the bus driver ordered Claudette to give up her seat. Claudette refused. As she later told Newsweek “I felt like Sojourner Truth was pushing down on one shoulder and Harriet Tubman was pushing down on the other. I was glued to my seat.”

Colvin was arrested for her civil disobedience and briefly put in jail. The NAACP and other civil rights groups considered rallying around Colvin’s case in their campaign against Alabama’s segregation laws before focusing efforts on Rosa Parks’ protest nine months later. Nevertheless, Colvin was one of four plaintiffs in the landmark Browder v. Gayle case of 1956, which ruled that the segregation laws of Montgomery and Alabama state were unconstitutional.

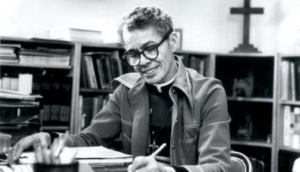

- Anna Murray was the first African-American woman to be ordained as an Episcopal priest.

This fiery woman exchanged letters with both Eleanor and Franklin Roosevelt for many years and was considered one of Eleanor’s dear friends. Although her work has rather sadly faded from view, Murray’s expertise in law was a vital part of the Civil Rights movement. She worked closely with icons like Thurgood Marshall and Rosa Parks, and was appointed by President Kennedy to the Presidential Commission on the Status of Women in the 1960s, where her work focused on “Jane Crow”: how discrimination against Black people particularly and deeply affected Black women, and the ways in which sexism and racism combined to affect Black women.

Murray died of cancer in 1985. In the last decade or so, her work has been brought back to light through various efforts, including making her childhood home a National Historic Landmark, and a blockbuster dual biography of Murray and Eleanor Roosevelt, The Firebrand and the First Lady.

- Matthew Henson was a key member of the first successful expedition to the North Pole and made seven separate voyages to the Arctic.

On April 9, 1909, Matthew Henson and Robert Peary arrived at the true North Pole. But getting there was no easy feat. The pair had made former attempts, but all had failed, including one where six members of the expedition team died of starvation. After they finally made it in 1909, Henson and Peary went on to explore the arctic for another two decades.

However, because this was the early 1900s, upon their return home from the North Pole, Peary was met with extensive praise, while Henson was barely noticed. In 1912, Henson published a memoir titled A Negro Explorer in the North Pole that detailed his Arctic adventures. It helped call attention to his role in the achievement, but he was still mostly forgotten.

In 1937, he finally received long-deserved recognition when he was invited to join the New York Explorer’s Club. It wasn’t until 2000, after his death, that Henson was awarded the National Geographic Hubbard Medal.

- Madam C.J. Walker was an African American entrepreneur who became America’s first female self-made millionaire.

Born in 1867 to former slaves on a Louisiana cotton plantation, Madam Walker rose in power to become America’s first female self-made millionaire. She did so through the creation of the Madam C.J. Walker Company. Headquartered in Indianapolis, Indiana, her company was a cosmetics manufacturer that specialized in beauty and haircare products for African American women.

Walker’s business prowess was matched only by her philanthropy and activism. She helped establish a YMCA in the Black community of Indianapolis and contributed funds to the Tuskegee Institute. Upon moving to New York, she joined the NAACP, donated generously to the NAACP’s anti-lynching fund, and commissioned the first Black architect in New York City to build Villa Lewaro, her home on the Hudson where great minds such as W.E.B. Du Bois and Booker T. Washington gathered to discuss social matters important to the African American community.

By the time of her death in 1919, she was known not only as a remarkably successful African American business owner, but one of America’s most successful entrepreneurs of all time.

- Billie Holiday’s famous “Strange Fruit” was originally a poem written by a school teacher.

In 1936, Lewis Allan published an anti-lynching poem called “Strange Fruit” in the Teacher Union magazine. Lewis Allan was a pseudonym for Abel Meeropol, a Jewish school teacher from the Bronx.

At the height of American lynchings, there were as many as 1,953 people killed by lynching a year. During the late 1800s and early 1900s, lynching had hit a peak, encouraged by the Jim Crow era, Reconstruction, and the Great Migration of Black Southern workers to northern cities.

Meeropol eventually set the poem to music. A few younger artists had picked up the song before, but it was Holiday who ultimately made it famous. She sang and recorded a version in 1939 that was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame. Holiday and Meeropol both were met with high praise. “Strange Fruit” is one of the most iconic songs of the Civil Rights Movement and retains its power to this day.

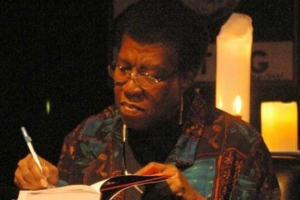

- Octavia E. Butler was dyslexic.

The woman who would become the first science-fiction writer to receive a MacArthur Fellowship and who would win countless awards for her work over a 40-odd year long career struggled with a “mild” case of dyslexia as a child.

Octavia E. Butler was raised primarily by her mother and grandmother after the early death of her father. A shy child whose dyslexia made her feel stupid, Butler took to hiding out in the library in her hometown of Pasadena. There, she discovered iconic science fiction magazines that sparked her desire to write. By the age of 12, she was at work on a story that would become the basis of one of her major series. Seventeen years later, her first book, Patternmaster, the first of that very series, was published.

- Benjamin Banneker taught himself astronomy and math to become America’s “First Known African American Man of Science”.

Benjamin Banneker was born a free man in 1731. He lived in Maryland with his mother, a free African American woman, and his father, a former slave. While researchers believe young Benjamin spent some time attending a Quaker school, he had little opportunity for formal education. So the young man taught himself—and soon revealed his brilliant mind.

Flexing his ability to calculate the positions of celestial objects at regular intervals, Banneker began publishing almanacs from 1792 through 1797. Each issue included Banneker’s astronomical calculations, weather predictions and tide tables, as well as poetry and writing on literature, medicine, and politics.

Banneker’s scholarly pursuits led to his correspondence with Thomas Jefferson. In a letter from 1791, Banneker respectfully challenged the then-Secretary of State’s view on slavery and the intellectual capacity of Black people. Jefferson responded, and Banneker later published their correspondence. 1791 also saw Banneker join a survey team tasked with establishing the boundaries of the nation’s capital. However, given the lack of historical documents, the exact nature of Banneker’s participation is difficult to discern.

- During her run for president, three separate assassination attempts were made on Shirley Chisholm.

“Unbought and unbossed.” Those words ring loudly as a mere speck of Shirley Chisholm’s legacy. Chisholm, born and raised in Brooklyn, became the first Black woman elected to Congress in 1968. After four years as the New York representative for the 12th congressional district (primarily the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood), Chisholm announced her run for the presidency. In that moment, she became the first Black candidate for president from a major party, and the first female candidate to run for the Democratic Party’s nomination.

Chisholm’s life was endangered as she vied for our nation’s highest office. The representative won a total of 28 delegates during her run. After stepping down from Congress, Chisholm taught at Mount Holyoke and Spelman College, both all-women colleges (Spelman is also a historically Black institution). In 2015, she was awarded a posthumous Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Barack Obama. In 2020, a statue of Chisholm was scheduled to be erected in Brooklyn’s Prospect Park, however due to the Covid pandemic the statue has yet to be erected.

- Dr. Mayme Clayton founded the Mayme A. Clayton Library & Museum in 1975.

Home to the Mayme Agnew Collection of African-American History and Culture, the MCLM contains millions of books, films, documents, artifacts, and art pieces which are products of Black contributions to the United States.

The museum was first started as the Western States Black Research Center; Dr. Clayton spent decades curating her historical collection on her own. Set up in a large garage within Clayton’s Los Angeles home, the collection was a library open to all. After some of the artifacts were damaged due to poor storage conditions, a campaign to rescue and relocate Dr. Clayton’s work finally paid off when the collection found its permanent home inside the former Los Angeles County Superior Courthouse in Culver City. It remains open for guided tours to this day.

- The 6888th Battalion was an all-Black, all-female unit of the military that delivered mail to World War II troops across England.

In February 1945, the 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion was established to deliver mail to American troops, government personnel, and volunteers abroad in England. At the time, many packages and letters were poorly addressed or sent to individuals with common names and little further direction.

Members of the service weren’t getting their mail, which had an outsized impact on morale. Officials estimated that, with the disarray of the postal warehouse, it would take around six months for the harrowing backlog to be sorted and delivered.

African-American women were granted the opportunity to travel to serve overseas in late 1944, and the 6888th Battalion was full of eager, well-trained recruits. Led by Major Charity Edna Adams, the women of the “Six Triple Eight” spent time in Oglethorpe, Georgia preparing for service—jumping over trenches, identifying enemy crafts, and marching. Mail delivery in a war zone did not come not without danger, and the women of the Battalion faced several close calls, injuries, and even some instances of death.

Though the reaction to this battalion was mixed, the Six Triple Eight was outstandingly efficient. The battalion worked in long shifts seven days a week and created a brand new tracking system for the mail they received. Rather than accomplishing the sorting of mail in the projected six months, the recruits blew through the task in three.

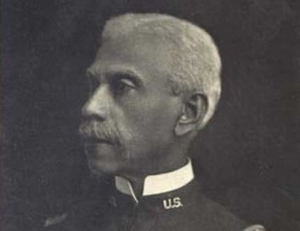

- Allensworth, California was an all-Black township—and the first of its kind.

The township was founded in 1908 by Colonel Allen Allensworth and a group of other African-American men. Allensworth was meant to be a refuge away from the oppression that Black people faced amidst society and aimed to be wholly self-reliant. The town of Allensworth ran largely off of agricultural pursuits, but contained its own small businesses and school district by 1912.

At the height of Allensworth’s success in the 1920s, there were around 300 residents. Severe drought and the discovery of arsenic in the water supply led to the loss of residents in the 1960s and 70s. In 1976, now empty, the town became a state historic park. You can visit its site daily between 9 am and sunset.

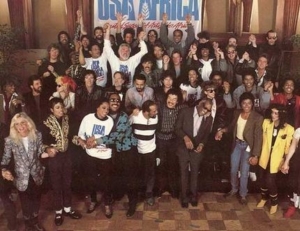

- The charity single “We Are the World” owes its creation and success to Black artists.

While most people today look back on the 1985 track as a cheesy supergroup relic of a different era, “We Are the World” sold over 20 million copies. The song swept across the world, raking in accolades and revenue and becoming the first single to ever be certified as multi-platinum. Three Grammys, an American Music Award, and a People’s Choice Award were bestowed upon the single, but most importantly it raised more than $63 million for aid in Africa and the United States.

The idea for the single was originated by activist Harry Belafonte. The King of Calypso was a key contributor moving forward as well, responsible in part for bringing Michael Jackson and Lionel Richie on board to write the single. One of the song’s two producers was legendary 28-time Grammy Award winner Quincy Jones. Among the singers on the track were soloists Stevie Wonder, Tina Turner, Diana Ross, and Dionne Warwick, as well as chorus members like Smokey Robinson, The Pointer Sisters, and several of the Jackson siblings.

After the earthquake that devastated Haiti in 2010, the song was re-recorded. Notable Black artists for the new release included Jennifer Hudson, Mary J. Blige, Janet Jackson, Usher, T-Pain, Kanye West, and many more.

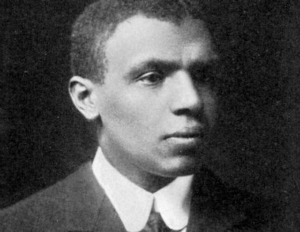

- John Baxter Taylor was the first African-American to win an Olympic gold medal.

While Taylor attended Central High School in Philadelphia, he ran track as the only Black athlete on the team. From there, he attended the Moses Brown Preparatory School in Rhode Island, flourishing on a team with an undefeated streak. When he enrolled in the Wharton School of Finance one year later, he joined the varsity track team, where he would come to break the intercollegiate record for the 440-yard run.

In the 1908 Olympics, Taylor competed in both the 400-meter relay final and the 1600-meter medley relay. The 400-meter relay was steeped in controversy, with officials claiming that one of the American runners fouled a British competitor—causing the gold medal to ultimately go to Britain. However, in the 1600-meter medley relay, Taylor ran the third leg of the race for his team and went down in history when he brought home the gold. Sadly, only five months after his triumph, Taylor passed away from typhoid fever complications.

- Langston Hughes’s great-uncle, John Mercer Langston, was the first Black man admitted to the Ohio bar.

John Mercer, born free in 1829, longed to be a lawyer for seemingly his whole life. Although denied law school admission, John began studying under local abolitionist lawyers in the 1850s. In 1854, a district court committee admitted him to the bar, calling him condescendingly “nearer white than black” as they did so.

John Langston went on to become the first Black man elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in Virginia.

- Black U.S. soldiers were recognized for their service by the French in WWI 90 years before the U.S. did the same.

The Harlem Hellfighters were a regiment of all-Black soldiers during World War I. They were sent to active duty in December 1917, deeded over to the French Army. There, the Hellfighters found themselves welcomed and integrated into the troops—a very different experience from their US Army time.

Over 170 men from the 369th were awarded the Croix de Guerre during the War. It was not until 2019 that the men were awarded a Congressional Gold Medal by the US in recognition of the risk they took and the rewards they secured.

- Betty Boop was based on a Black woman.

Photo Credit: L: “Do Tell”. James Van Der Zee, 1930. R: Fleischer Studios

Although inspiration for Boop’s image came directly from Helen Kane, a popular flapper and film star, Kane’s own public persona was a direct rendition of Baby Esther—a stage name for one Esther Jones. In fact, when Kane sued Betty Boop’s creator for stealing her voice and catchphrase, a recording of Baby Esther’s performance proved that she couldn’t claim the style was her own, singular creation. Despite this case, Baby Esther fell into historical obscurity after the 1930s.

- Cathay Williams, once enslaved, disguised herself as a man to serve in the U.S. Army after the Civil War.

In 1861, Cathay Williams was freed from service at the Johnson Plantation by the Union Army… and immediately pressed into service as a cook and washerwoman for the troops.

Despite being forced to travel around the country with General Philip Sheridan’s troops for five years, Williams found a new sense of purpose in working with the troops—so much so that she enlisted in the 38th Infantry Regiment in 1866 as one “William Cathay”.

- Ralph Bunche was the first person of color and the first African-American to receive a Nobel Peace Prize.

Bunche, a diplomat and political scientist, began working with the United Nations as early as 1944, as the form of the coalition began to become clear in the waning days of World War II. He, along with Eleanor Roosevelt, was responsible for the creation of 1948’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

His Nobel Prize was given in recognition of this work amongst the Arab-Israeli conflict in the late 1940s. Bunche was the UN’s chief mediator for the conflict and negotiated the 1949 Armistice Agreements. The following year, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

- Harriet Tubman was the first woman to lead a U.S. military operation.

In 1863, Tubman led a regiment in the Raid on Combahee Ferry. Tubman planned and carried out the attack, which freed some 750 enslaved people and laid waste to the Confederates’ encampment. A few weeks later, the 54th Massachusetts Regiment, an all-Black volunteer regiment, executed a similar raid up the river in Darien, Georgia.

- Ida B. Wells’s anti-lynching pamphlets helped usher in a new era of journalism.

You may be familiar with the terms “muckrakers” or “yellow journalism”. At the turn of the 20th century, journalists began writing vividly-described stories about horrific practices around the country and the world—Nellie Bly’s Ten Days in a Mad-house and Ida Tarbell’s The History of the Standard Oil Company are two classics of the genre. But without Wells’s Southern Horrors, a 1892 pamphlet detailing lynching accounts throughout the United States and how those lynchings were enacted to punish Black people who threatened white power structures. Her investigative journalism gave rise to new methodology.

- Jackie Robinson’s brother was also an elite athlete.

Although Jackie Robinson is the one remembered by history, older brother Matthew “Mack” Robinson was also an exemplary athlete. In fact, at the 1936 Summer Olympics, when Jesse Owens obliterated the world record for the 200 meter dash, Mack also broke the previously held record. Since he won the silver medal to Owens’s gold—coming in second by only 0.4 seconds—the elder Robinson’s name failed to make the same mark in history as his brother and his competitor.

- Thurgood Marshall’s journey to the Supreme Court began as a child.

From a young age, Marshall’s parents emphasized the importance of education, the Constitution, and the rule of law. His father, a railroad porter, took Thurgood and his brother to watch court cases in their hometown of Baltimore. After dinner, Marshall’s mother, a schoolteacher, would join the three in a debate about the cases they’d watched that day and other current events.

Marshall credited his father with turning him into a lawyer, saying that his father “did it by teaching me to argue, by challenging my logic on every point, by making me prove every statement I made.” Marshall would become the first Black Supreme Court justice in 1967, nominated by President Johnson.

- Lincoln University was the first historically Black university to grant degrees in the United States.

Still in operation today, this small public university in Pennsylvania recently made headlines after MacKenzie Scott donated $20 million to the school. Lincoln (then called Ashmun Institute) welcomed its first students in 1854. Many prominent thinkers and creators have walked its halls, including Medal of Honor recipient and Civil War veteran Christian Fleetwood, class of 1860; poet Langston Hughes, class of 1929; and Thurgood Marshall, the first Black justice on the Supreme Court, class of 1930.