The Ruby and Calvin Fletcher Museum of African American History

952 East Broadway

By Andréa Byrne

Editor

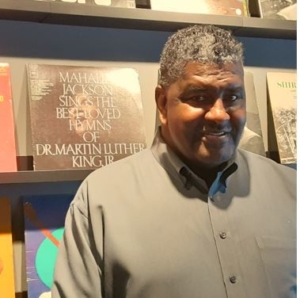

It takes many things to see a particular dream through to completion: vision and passion, certainly, but also a keen sense of the past and a personal understanding of how it affects the present and the future. Jeffrey Fletcher possesses all these qualities, and his dream, The Ruby and Calvin Fletcher Museum of African American History, now stands at 952 East Broadway here in Stratford. It is the first such museum in New England.

It takes many things to see a particular dream through to completion: vision and passion, certainly, but also a keen sense of the past and a personal understanding of how it affects the present and the future. Jeffrey Fletcher possesses all these qualities, and his dream, The Ruby and Calvin Fletcher Museum of African American History, now stands at 952 East Broadway here in Stratford. It is the first such museum in New England.

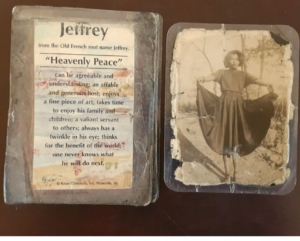

His journey with this project began with the over 400 artifacts his mother, Ruby, collected during her long lifetime. They filled the house in Colchester where Jeffrey grew up, and when he went to college they began to spill over into his room. While the collection was orderly, at the time he considered it just so much useless junk, and something his father Clifford indulged her in. His parents were jokingly but lovingly referred to as the junk-collectors Fred Sanford and Lamont, in the old TV show Sanford and Son.

Jeffrey has had a winding career path. After he received a degree in psychology from the University of New Haven he worked for the Connecticut Department of Mental Health for fourteen years. He also played semi-pro basketball, and joined the New Haven police force in 1995, retiring in 2013.

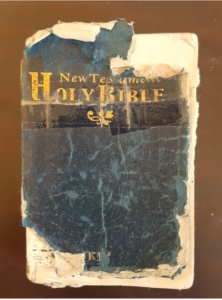

Ruby died in 2006, but she had begun to chronicle her entire collection, as if she’d had a premonition of her death. “I realized then that all these items were telling a story—not only my mother’s, but a story of our country,” Jeffrey said. She and Clifford had escaped the Jim Crow south to come to Connecticut, and the family they raised here is close and deeply spiritual. Jeffrey carries a small, well-worn Bible from his mother.

“I never leave my house without it,” he says. “Through all my years on the police force it was always in my shirt pocket, right over my heart.”

In 2007, Jeffrey made use of his mother’s collection, and began collecting items of his own to enhance the telling of the African American experience. He spoke at schools and to various groups, always with the desire to show the chronological journey of that experience. After his retirement from the police force he expanded the presentations and began to look in earnest for a ‘home’ to fulfill that desire. While other towns rejected the idea, he was welcomed by Mayor Laura Hoydick and theown of Stratford.

In 2007, Jeffrey made use of his mother’s collection, and began collecting items of his own to enhance the telling of the African American experience. He spoke at schools and to various groups, always with the desire to show the chronological journey of that experience. After his retirement from the police force he expanded the presentations and began to look in earnest for a ‘home’ to fulfill that desire. While other towns rejected the idea, he was welcomed by Mayor Laura Hoydick and theown of Stratford.

Two years ago he began to convert the historic house on East Broadway and the museum was opened on October 30th, 2021, with some 550 people in attendance despite a dreadful downpour. At the end of the downpour a brilliant rainbow appeared. Perhaps a nod from Ruby?

Now for a brief tour to introduce you to a sample of what the museum offers. Jeffrey’s intent is to show the factual history but not to lay blame for the past. He feels that would deny people the opportunity to truly take in and process what they are seeing. He believes the people of today are only responsible for themselves, not the actions of their forebears.

This tour through time begins in 1619 Africa in a room that features beautifully carved wooden figures and an elaborate beaded headdress. We then move into a slave ship to, as Jeffrey puts it, ‘experience the souls transported on those vessels’. The flooring planks are actual 1860 ship boards, and a cut-away of tiny bunks shows a figure locked in place by a shackle that was actually used in that time and way. While the captives were allowed on deck for very brief moments, they continued to be shackled to prevent escape. An accurate model of the Amistad in this room served in making the full-sized replica that exists today in New Haven harbor.

This tour through time begins in 1619 Africa in a room that features beautifully carved wooden figures and an elaborate beaded headdress. We then move into a slave ship to, as Jeffrey puts it, ‘experience the souls transported on those vessels’. The flooring planks are actual 1860 ship boards, and a cut-away of tiny bunks shows a figure locked in place by a shackle that was actually used in that time and way. While the captives were allowed on deck for very brief moments, they continued to be shackled to prevent escape. An accurate model of the Amistad in this room served in making the full-sized replica that exists today in New Haven harbor.

One wall of the room is a sweeping map of the routes from Africa to destinations in Brazil, the Caribbean and the United States, and the number of people captured and taken there totals in the millions. Most were taken to the Caribbean and Brazil. Jeffrey’s great-great grandmother, Miranda Reeves, who died at the age of 114 in 1983, was the daughter of two slaves. He says her mind was sharp with memories and stories right to the end.

The next room holds information on Plantation Life in the 1800’s with want-ads offering people for sale as well as offering rewards for runaway enslaved people. There are actual ‘control devices’ exhibited, although other than the whip, they were seldom used because the plantation owners spent a good deal of money purchasing these people. It didn’t make financial sense to injure them to the extent they couldn’t do what they were bought for.

We move through a space that signifies the Underground Railway and on into late 1800’s and early 1900’s ads and items that played to the stereotypical idea of the Negro population being slow and lazy, or jolly and content with their less-than status.

From there we go to a room that features the Pullman Porters. When industrialist George Pullman created luxury sleeper cars for train travel, he hired former enslaved men to be the porters attending to travelers. He reasoned that they knew better than anyone how to serve and cater to the wealthy customers’ wants and needs, and do it for not much pay. Because he thought passengers wouldn’t have time or interest in learning the porters’ names, all had ‘George’ on their name tags. Actor Jacky Gleason, who always traveled by train, was one who took the time to ask each porter’s real name—and remember it.

There’s a large photograph of A. Philip Randolph, who organized the first African American union, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. There are also authentic uniforms on display from a job that became a matter of pride for many, and led to opportunities not open to others.

There’s a large photograph of A. Philip Randolph, who organized the first African American union, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. There are also authentic uniforms on display from a job that became a matter of pride for many, and led to opportunities not open to others.

The next room deals with entertainment and resembles a movie theater of days gone by. In addition to a wall of period movie posters, there’s a large screen with running segments of The African Queen and Gone With The Wind opposite a row of old wooden theater seats.

We step from there into the Founder’s Hallway. This area is dedicated to Mike and Sue Koperwhats, whose home this had been for many years until Mike’s death in 2017. Mike was a beloved educator in Stratford and to honor his commitment to education there is a photograph of him, and near that a plaster sculpture from the mid-1860’s of ‘Uncle Ned’s School’, depicting a young girl teaching an old man to read.

We then go through a short hall to a section dedicated to the Tuskegee Airmen, a nickname given to the first squadron of Black pilots which was created in 1941 during World War II. The name also encompassed navigators, bombardiers, mechanics, instructors, crew chiefs and other support personnel.

The military was still segregated but with the help of the NAACP, labor union leader A. Philip Randolphm and others, including Eleanor Roosevelt, the government was persuaded to designate funds for training African American pilots at Tuskegee Air Field near the historic Tuskegee Institute, now known as Tuskegee University. These pilots made a significant contribution to winning the war with their skills, courage and perseverance. One of the airmen featured is Edward Thornton Dixon, who came from Hartford. Henry E. Fletcher, a distant cousin of Jeffrey’s, was in the same unit.

Next stop is the Civil Rights room with images of Dr. Martin Luther King and other notable people who so bravely stood for the rights which should be afforded to everyone. There are three doors with signage that reads ‘white men’, ‘white women’, and ‘colored men’. Not even a door for ‘colored women’—they were to use the ‘colored men’s’ room and take their chances of being walked in on. This exhibit demonstrates the clear divisions there were at the time, and that still exist today in some minds.

There is a fourth door in the exhibit. It symbolizes the experience Jeffrey had at a Starbucks coffee shop in New Haven when he was a policeman. He and his colleagues were there and after he asked the barista three times for the bathroom key she said she didn’t have it, it was in the safe. He left to find another bathroom and when he returned his colleagues said she’d given a key to a white man. When he confronted her with that she ignored him and walked away. He filed a complaint with Starbucks, only to be told there was no one working that day who fit the description he gave. When he informed them he was engaging a lawyer they admitted there had been a person there of that description, but she quit when confronted by management about the incident. Soon after that he was offered a non-disclosure agreement with a ‘goodwill compensation’ of $3,000.

There is a fourth door in the exhibit. It symbolizes the experience Jeffrey had at a Starbucks coffee shop in New Haven when he was a policeman. He and his colleagues were there and after he asked the barista three times for the bathroom key she said she didn’t have it, it was in the safe. He left to find another bathroom and when he returned his colleagues said she’d given a key to a white man. When he confronted her with that she ignored him and walked away. He filed a complaint with Starbucks, only to be told there was no one working that day who fit the description he gave. When he informed them he was engaging a lawyer they admitted there had been a person there of that description, but she quit when confronted by management about the incident. Soon after that he was offered a non-disclosure agreement with a ‘goodwill compensation’ of $3,000.

“It’s not about the money,” he said. “It’s not about the dollars. It’s about acknowledging the wrong and how do we move forward to not let this happen again?” (You can read his entire account on the museum website: https://www.africanamericancollections.com/ )

The final room is dedicated to music with a display of 33rpm albums and other items that were part of Ruby’s collection. Mounted on the wall are two guitars that had been his father’s, one of which was hand-made by Calvin. Calvin, who died in 2010, could not read music but had the great gift of being able to play a song flawlessly after hearing it only once or twice.

The museum is sponsored by Shearman & Sterling, LLP, an international law firm based in New York. They have a deep historic connection to Stratford in that a co-founder of the firm was John W. Sterling. Born in Stratford in 1844, he became a well-respected, wealthy and charitable lawyer. In 1886 he built the mansion that we know as Sterling House to use as a weekend getaway for himself and his sisters. When he died in 1918 he left eighteen million dollars to his alma mater, Yale University.

There’s so much to be learned beyond the glimpses given here. Jeffrey wanted this museum to be located in his home state so that children and adults here could benefit without distant and expensive excursions to the Smithsonian or elsewhere. Interested students from Bunnell and Stratford High Schools volunteer not only during weekend museum hours, but also to work behind the scenes with the exhibits and have a genuine hands-on and intimate experience with this history. The basic staff is small, consisting of Jeffrey Fletcher, his assistant Elizabeth O’Rourke, and graphic designer Christine Bliss-LaCroix.

It’s a testament to the love and admiration that Jeffrey has for his late parents that he named this museum for them. In their memory, he wants people to see actual historical items and match them with what they read in textbooks, history books or novels. He wants them to understand. And as he says, “Now is the time; this is the place.”

Museum hours are Monday, Wednesday and Thursday, 10:00am to 5:00pm, and Saturday, 10:00am to 3:00pm. The museum is free of charge but donations and additional sponsors are always welcomed.