By Barbara Heimlich

Editor

Sources: HISTORY ; Ashley Leath, Country Living; Lesley Kennedy

How are you going to ring in 2024? Are you going to a party? Sitting on the couch with a bottle of champagne and a good friend? Watching the ball drop on the multiple stations carrying New Year’s Countdowns?

No matter how you ring in the New Year, here are some facts you may find interesting, or, if a cook, inspirational for a New Year’s feast.

Happy New Year!

Who Is Baby New Year?

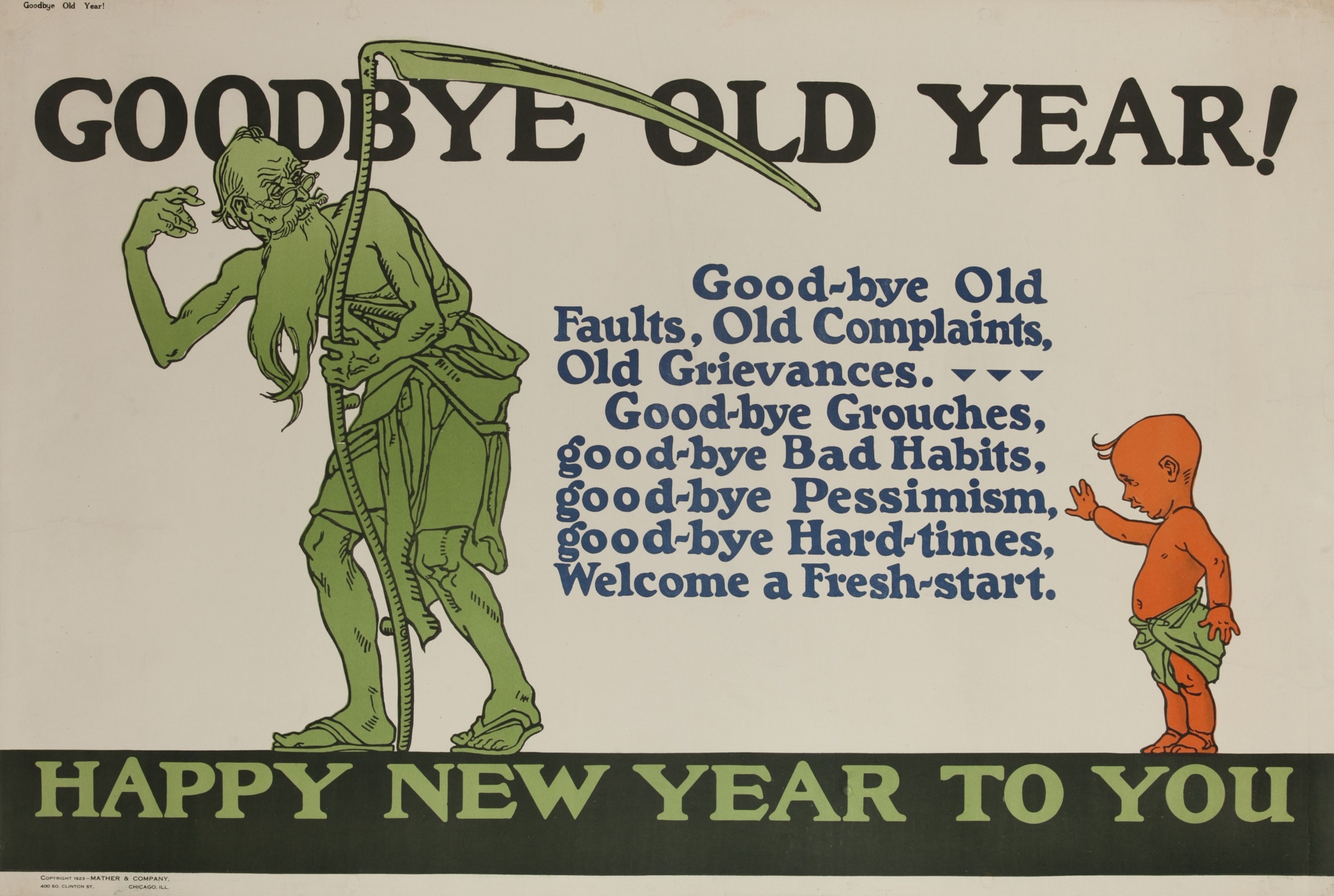

Baby New Year is an illustration of a baby, sometimes depicted with a hat or sash, who represents the birth of the new calendar year. He is often seen alongside Father Time, the now-grown Baby New Year from the previous year. At the end of each year, Father Time bestows the wisdom and knowledge he’s learned over the course of the year to the newly born Baby New Year, who will spend the year growing and learning before passing on his knowledge as Father Time next January 1, and so forth. (Father Time is often seen with a scythe because he is based on the Roman god Saturn, who was tied to farming and was celebrated with harvest-time festivities. The scythe is a symbol of the endurance of time, which will never stop and will eventually “cut down” all living things.) Together, the illustrated figures of Baby New Year and Father Time are personifications of the passage of time giving way to the vibrancy of a brand-new year.

When was the first New Year’s Eve ball dropped in New York’s Times Square?

An estimated 1 billion people around the world watch each year as a brightly lit ball descends down a pole atop the One Times Square building at midnight on New Year’s Eve. The world-famous celebration dates back to 1904, when the New York Times newspaper relocated to what was then known as Longacre Square and convinced the city to rename the neighborhood in its honor. At the end of the year, the publication’s owner threw a raucous party with an elaborate fireworks display.

When the city banned fireworks in 1907, an electrician devised a wood-and-iron ball that weighed 700 pounds, was illuminated with 100 light bulbs and was dropped from a flagpole at midnight on New Year’s Eve. Lowered almost every year since then, the iconic orb has undergone several upgrades over the decades and now weighs in at nearly 12,000 pounds. In more recent years, various towns and cities across America have developed their own versions of the Times Square ritual, organizing public drops of items ranging from pickles (Dillsburg, Pennsylvania) to possums (Tallapoosa, Georgia) at midnight on New Year’s Eve.

What are some traditional New Year’s foods?

Champagne, noise makers and confetti are all New Year’s Eve staples. But, in some parts of the country and the world, so are black-eyed peas, lentils, grapes and pickled herring. Hailing from the Low Country of South Carolina to Japanese noodle houses to Pennsylvania Dutch homes, these are seven lucky dishes traditionally eaten around the New Year to bring good fortune.

At New Year’s Eve parties and celebrations around the world, revelers enjoy meals and snacks thought to bestow good luck for the coming year. In Spain and several other Spanish-speaking countries, people bolt down a dozen grapes—symbolizing their hopes for the months ahead—right before midnight. The Spanish tradition las doce uvas de la suerta, aka the 12 lucky grapes, holds that eating 12 grapes at the stroke of midnight—one for each chime of the clock—will bring good luck in the coming year. Each grape signifies one month, and, according to the superstition, failing to finish all 12 in time will mean misfortune in the year to come. NPR dates the custom’s start in the 1880s, with newspapers reporting Madrid bourgeoisie swiping grape and champagne traditions from the French.

In many parts of the world, traditional New Year’s dishes feature legumes, which are thought to resemble coins and herald future financial success; examples include lentils in Italy and black-eyed peas in the southern United States.

Italian New Year’s Eve feasts can mean multiple courses served over several hours. One dish in the massive spread said to bring especially good luck: lentils. Round and shaped like a coin, they’re a symbol of prosperity, and are often served with pork sausage.

Because pigs represent progress and prosperity in some cultures, pork appears on the New Year’s Eve table in Cuba, Austria, Hungary, Portugal and other countries. Ring-shaped cakes and pastries, a sign that the year has come full circle, round out the feast in the Netherlands, Mexico, Greece and elsewhere.

In Sweden and Norway, pickled herring. Fish, symbolic of fertility, long life and bounty (plus the color silver represents fortune), is a popular New Year’s Eve dish in many cultures, and especially so for those of Scandinavian, German and Polish descent. Pickled herring, a small oily fish, is often served at New Year’s Eve smorgasbords.

Herring has been a standard Scandinavian, Dutch and Northern European dish since the Middle Ages, due in part to its abundance—which it has become symbolic of, making it a popular, lucky New Year tradition. It’s especially carried on in the U.S. in states such as Minnesota, Wisconsin and Iowa, which have large Norwegian populations.

Ringing in the year with toshikoshi soba, a soup with buckwheat “year-crossing” noodles, is a New Year’s Eve tradition in Japan steeped in tradition and now practiced in the United States. According to The Japan Times, toshikoshi means “to climb or jump from the old year to the new.”

The long, thin noodles symbolize a long, healthy life, and date back to the 13th or 14th century, “when either a temple or a wealthy lord decided to treat the hungry populace to soba noodles on the last day of the year.”