“Traveling thru the Dark”

By Norah Christian

Traveling Through the Dark

By William Stafford

Traveling through the dark I found a deer

dead on the edge of the Wilson River road.

It is usually best to roll them into the canyon:

that road is narrow; to swerve might make more dead.

By glow of the tail-light I stumbled back of the car

and stood by the heap, a doe, a recent killing;

she had stiffened already, almost cold.

I dragged her off; she was large in the belly.

My fingers touching her side brought me the reason—

her side was warm; her fawn lay there waiting,

alive, still, never to be born.

Beside that mountain road I hesitated.

The car aimed ahead its lowered parking lights;

under the hood purred the steady engine.

I stood in the glare of the warm exhaust turning red;

around our group I could hear the wilderness listen.

I thought hard for us all—my only swerving—,

then pushed her over the edge into the river.

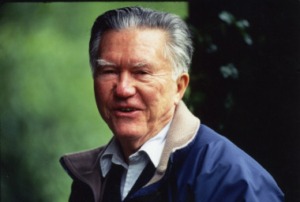

William Stafford was born in 1914 in Hutchinson, Kansas. He was the oldest of three children. To help out the family during the depression, he worked in sugar beet fields and as an electrician’s apprentice. Later, while studying at the University of Kansas, he was drafted into the army. As a registered conscientious objector, he worked in the Civilian Public Service camps from 1942 to 1946, earning $2.50 per month in the forestry and soil conservation divisions in Arkansas, California, and Illinois.

After the war, he taught at Indiana’s Manchester College, Lewis and Clark University in Oregon, and San Jose State in California. At 48, he published his first volume of poetry. In 1970 he was appointed Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress (now known as “Poet Laureate”). On the morning of his death, in 1993, he wrote a poem with these lines—

“ ‘You don’t have to

prove anything,’ my mother said. ‘Just be ready

for what God sends.’ “

William Stafford is known for his simple, plain-spoken language. He believed in the teaching power of Nature. Reading his poem “Traveling through the Dark,” we are rather shocked by the ending when the narrator pushes the dead but pregnant doe into a river ravine. Reading the poem, many of us might have thought (at least I did) that the the fawn would be saved, that the narrator would take out his hunting knife, perform a Caesarian, take the living fawn from the dead doe, and raise the fawn as his pet to live happily ever after in his backyard. Something like that. (Oh, how we long for happy endings!)

But the narrator hesitates. He knows it’s best to roll her into the canyon in order to avoid more dead by accident. Still, he hesitates. The fawn. He hears the wilderness listening, just as he is listening to the wilderness. The glare of the car’s rear lights are turning the exhaust fumes red. He stands there in a kind of mini-hell of indecision. He thinks hard “for us all.” And then he pushes the doe with fawn into the canyon.

But what is this all supposed to mean?

Stafford himself once explained that “Traveling through The Dark” is not a poem supporting his position on anything. (I think here, weirdly, of a pro-abortion position.) Stafford said, “…it’s just a poem that grows out of the plight I am in as a human being.” And his plight is ours. We are all “traveling through the dark,” feeling our way, trying to know what is the greater good, what is best for us all. We are constantly faced with choices over which we think hard before we choose. We listen to our inner moral sense. We listen to our good judgment. We listen to the wilderness and our animal instincts. And then we make our choice. We hope it’s a good one.