After Making Love We Hear Footsteps

By Norah Christianson

After Making Love We Hear Footsteps

~ By Galway Kinnell

For I can snore like a bullhorn

or play loud music

or sit up talking with any reasonably sober Irishman

and Fergus will only sink deeper

into his dreamless sleep, which goes by all in one flash,

but let there be that heavy breathing

or a stifled come-cry anywhere in the house

and he will wrench himself awake

and make for it on the run—as now, we lie together,

after making love, quiet, touching along the length of our bodies,

familiar touch of the long-married,

and he appears—in his baseball pajamas, it happens,

the neck opening so small he has to screw them on—

and flops down between us and hugs us and snuggles himself to sleep,

his face gleaming with satisfaction at being this very child.

In the half darkness we look at each other

and smile

and touch arms across this little, startlingly muscled body—

this one whom habit of memory propels to the ground of his making,

sleeper only the mortal sounds can sing awake,

this blessing love gives again into our arms.

Galway’s poem is so lovely, humorous, simple, clear, nothing really needs to be said about it. But I will say something anyway, because I used to teach. Galway writes here that he can make any kind of noise at night and it will not wake his son. But let it be the sounds of love-making, and Fergus, his sleeping son, will “make for it on the run” to climb into bed with his mum and da. I only tell you this, which I know you already have understood, because I’ve had students who thought that it was the young boy who made the “come-cry” (???), that the mother is the one speaking (she snores like a bullhorn???), and that it is she who rushes to him to comfort him in his “distress.” One student thought the parents were “frustrated,” another thought them “resentful.” (Freud would understand those students to have parent-child issues.) Anyway, wherever there are words, there will be misinterpretations.

“After Making Love We Hear Footsteps” is a love poem. It begins with love-making. It continues on with love (“we lie together,/ after making love, quiet, touching along the length of our bodies,/ familiar touch of the long-married….”). And when Fergus climbs into bed with them, the parents “…look at each other/and smile/and touch arms across this little, startlingly muscled body.” Love. Fergus’s “habit of memory,” his primordial memory of his parents’ love-cry at the moment of his inception, propels the boy to the place of his creation, the “ground of his making.” And it is love that delivers into his parents’ arms the blessing that is their son.

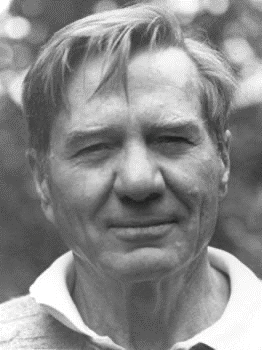

Galway Kinnell (1927 – 2014) was born in Providence and grew up in my hometown of Pawtucket, a small mill town in Rhode Island. (He once said it was the “stultifying nature of the place” that drove him to verse.) He studied at Princeton, earned his M.A. from the University of Rochester, and served in the U.S. Navy. He then traveled extensively, especially in France and Iran, all the while writing, writing, writing. Returning to the U.S., he became involved for most of the 1960’s with the Civil Rights Movement, working on integration and helping to register black voters in Louisiana (which got him beaten and then jailed for five days). He supported the movement against the Viet Nam war, and in 1968, he signed the “Writers and Editors War Tax Protest” pledge, voting to withhold federal tax payments in protest against the Vietnam War.

Galway Kinnell won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1982 and split the National Book Award for Poetry with Charles Wright. From 1989 to 1993 he was Poet Laureate for the state of Vermont, where he lived for many years.

Although we came from the same hometown, I never knew Galway until we met at the Pawtucket Armory Arts Center in 2005. (Pawtucket had come up some in the world by then.) We two, being poet-products of Pawtucket, were honored by being invited there to read our poetry together. I was in such a state of awe and reverence to be on the same stage as Galway Kinnell, I barely had any spit in my mouth. It was a grand night. On another occasion, we had dinner together in Simsbury. Galway was a lovely, gentle man—humble, funny (how can an Irishmen not be funny?), and very, very kind. He is also a wonderful poet. I say “is” because he is, will always be, with us.

Lovely