Women who Captured their Surroundings

Name: Alma Thomas, AKA Alma Woodsey Thomas

Born in Columbus, Georgia, Died in Washington, DC

During the 1950s Thomas attended art classes at American University in Washington As a black woman artist, Thomas encountered many barriers; she did not, however, turn to racial or feminist issues in her art, believing rather that the creative spirit is independent of race or gender.

Alma Thomas began to paint seriously in 1960, when she retired from her thirty-eight- year career as an art teacher in the public schools of Washington, D.C. In the years that followed she would come to be regarded as a major painter of the Washington Color Field School. Alma Thomas emerged as an exuberant colorist, abstracting shapes and patterns from the trees and flowers around her. Her new palette and technique—considerably lighter and looser than in her earlier representational works and dark abstractions—reflected her long study of color theory and the watercolor medium.

Although Thomas progressed to painting in acrylics on large canvases, she continued to produce many watercolors that were studies for her paintings. Thomas’s personalized mature style consisted of broad, mosaic-like patches of vibrant color applied in concentric circles or vertical stripes. Color was the basis of her painting, undeniably reflecting her life-long study of color theory as well as the influence of luminous, elegant abstract works by Washington-based Color Field painters such as Morris Louis, Kenneth Noland, and Gene Davis.

Thomas was in her eighties when she produced her most important works. Earliest to win acclaim was her series of Earth paintings—pure color abstractions of concentric circles that often suggest target paintings and stripes. Done in the late 1960s, these works bear references to rows and borders of flowers inspired by Washington’s famed azaleas and cherry blossoms. The titles of her paintings often reflect this influence. In these canvases, brilliant shades of green, pale and deep blue, violet, deep red, light red, orange, and yellow are offset by white areas of untouched raw canvas, suggesting jewel-like Byzantine mosaics.

Thomas was in her eighties when she produced her most important works. Earliest to win acclaim was her series of Earth paintings—pure color abstractions of concentric circles that often suggest target paintings and stripes. Done in the late 1960s, these works bear references to rows and borders of flowers inspired by Washington’s famed azaleas and cherry blossoms. The titles of her paintings often reflect this influence. In these canvases, brilliant shades of green, pale and deep blue, violet, deep red, light red, orange, and yellow are offset by white areas of untouched raw canvas, suggesting jewel-like Byzantine mosaics.

Man’s landing on the moon in 1969 exerted a profound influence on Thomas, and provided the theme for her second major group of paintings. In 1969 she began the Space or Snoopy series so named because “Snoopy” was a term astronauts used to describe a space vehicle used on the moon’s surface. Like the Earth series these paintings also evoke mood through color, yet several allude to more than a color reference. In Snoopy Sees a Sunrise of 1970, she placed a circular form within the mosaic patch of colors and accented it with curved bands of light colors. Blast Off depicts an elongated triangular arrangement of dark blue patches rising dramatically and evocatively against a background of pale pinks and oranges. The majority of Thomas’s Space paintings are large sparkling works with implied movement achieved through floating patterns of broken colors against a white background.

In her last paintings, Thomas employed her characteristic short bars of color and impasto technique. The tones, however, became more subdued, and the formerly vertical and horizontal accents of Thomas’s brush strokes became more diverse in movement, and included diagonals, diamond shapes, and asymmetrical surface patterns. During the artist’s final years, the crippling effects of arthritis prevented her from painting as often as she wanted.

In 1972 she was honored with one-woman exhibitions at the Whitney Museum of American Art and at the Corcoran Gallery of Art; that same year one of her paintings was selected for the permanent collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. Before her death in 1978, Thomas had achieved national recognition as a major woman artist devoted to abstract painting.

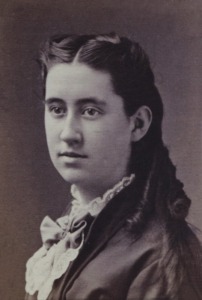

Name: Mary Rogers Williams (September 30, 1857 – September 17, 1907)

Education: Smith College

Revolutionary artist Mary Rogers Williams, a baker’s daughter from Hartford, biked and hiked from the Arctic Circle to Naples, exhibited from Paris to Indianapolis, trained at the Art Students League, chafed against art world rules that favored men, wrote thousands of pages about her travels and work, taught at Smith College for nearly two decades, but sadly ended up almost totally obscure. Mary and her surviving sisters Lucy, Abby and Laura were all-star students at Hartford Public High School.

She was second in command of Smith College’s art department from 1888 to 1906 under Dwight William

Tryon and earned acclaim for paintings of her native New England and scenes from her wide travels in Europe, from Norway to the Paestum ruins south of Naples. She often depicted high horizons, whether in meadows or medieval hill towns, under ribbons of sky.

A member of the New York Woman’s Art Club, she exhibited there (1899, 1902, 1903) and at venues including the American Water Color Society, Art Association of Indianapolis, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Gill’s Art Galleries, Springfield, Massachusetts, American Girl’s Club in Paris, National Academy of Design, New York Water Color Club, Society of American Artists, Macbeth Gallery—she also commissioned “aquarium”-like frames from Macbeth, with a glass layer an inch away from the delicate pastel surface) and Paris Salon.

Commemorative posthumous shows were held in 1908 and 1909 at the Philadelphia Water Color Club (at Pennsylvania Academy), New York Water Color Club and Wadsworth Atheneum and Hartford Art Society in Hartford. Publications that praised her include the New York Times, the Hartford Courant, the Springfield Republican and various art magazines. In 1894, in an article in the Quarterly Illustrator, the novelist.

Elizabeth Williams Champney described Mary Williams as “an artist with rare poetic instinct and feeling” and “a woman of conscience as well as feeling, and of a fine scorn for all shams.” The Champney article added, “When asked what style she proposed to adopt, she replied: ‘If I cannot have a style of my own, I trust I may be spared an adopted one.'”

Family and friends kept her paintings inventory together, and most remain in a private New England collection. Institutions that have her work include the Smith College Museum of Art, Connecticut Landmarks and the Connecticut Historical Society–the latter both own Williams’ portraits of her friend and patron, the New Haven antiquarian George Dudley Seymour.

Williams’ diary, photos of her and thousands of pages of her correspondence are in a private New England collection. A few letters about and from her are in the Macbeth Gallery papers at the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art and the George Dudley Seymour papers at Yale and at the Connecticut Historical Society.

Georgia Totto O’Keeffe (November 15, 1887-March 6, 1986)

American Modernism Painter

Education: School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Art Students League of New York, University of Virginia, Teachers College, Columbia University

Awards: National Medal of Arts (1985), Presidential Medal of Freedom (1977) Edward MacDowell Medal (1972)

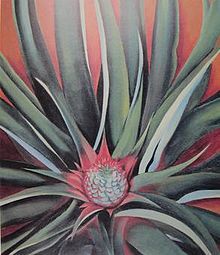

Georgia Totto O’Keeffe was an American artist. She was known for her paintings of enlarged flowers, New York skyscrapers, and New Mexico landscapes. O’Keeffe has been recognized as the “Mother of American modernism”. One of the first female painters to achieve worldwide acclaim from critics and the general public, Georgia O’Keeffe was an American painter who created innovative impressionist images that challenged perceptions and evolved constantly throughout her career.

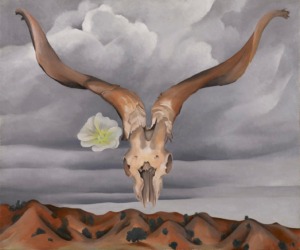

In 1929, seeking solitude and an escape from a crowd that perhaps felt artistically and socially oppressive, O’Keeffe traveled to New Mexico and began an inspirational love affair with the visual scenery of the state. For 20 years she spent part of every year working in New Mexico, becoming increasingly interested in the forms of animal skulls and the southwest landscapes.

While her popularity continued to grow, O’Keeffe increasingly sought solace in New Mexico. Her painting Ram’s Head with Hollyhock encapsulates so much novelty while still maintaining with her classic aesthetic of magnifying and showing the beauty in small, natural details. While her interest in the southwest increased, so did the value of her paintings in the New York galleries.

In 1935 – after a period of personal and professional stress during which she was absent from New Mexico and nearly abandoned her art – O’Keeffe returned to the

Southwest. She was rejuvenated by the dramatic landscaped of the high desert country, and it showed in her canvases from that summer’s sojourn. Ram’s Head with Hollyhock announced the new freedom and inspiration; the design continues the formal play and the interest in evocative combinations of subjects first tackled in the early 1930s, but now handled with unprecedented assuredness. The enigmatic juxtaposition of skeletal, flora, and landscape images – a virtual catalogue of the subjects that had earlier garnered her acclaim – provoked new interest in O’Keeffe’s work, especially after the fallow period that had immediately preceded their introduction in January 1936.