Sources: National Archives; New England Lighthouses: A Virtual Guide; LighthouseFriends.com; Wikipedia; The History of Lordship, “Stratford Point Lighthouse Keepers and Stories – The light must never go out”; Lighthouses – US Coast Guard Historian’s Office

By Barbara Heimlich

Editor

On Sunday, September 4th and September 11th, from 12 p.m. until 3 p.m., the Stratford Historical Society, in conjunction with the Town of Stratford, will be hosting a limited Historical Open House of the Stratford Point lighthouse property.

On Sunday, September 4th and September 11th, from 12 p.m. until 3 p.m., the Stratford Historical Society, in conjunction with the Town of Stratford, will be hosting a limited Historical Open House of the Stratford Point lighthouse property.

A slideshow presentation will be available of the interior of the lighthouse and an historical walking tour will be offered of Stratford Point. Three program times slots are available at 12 p.m., 1:30 p.m. and 3.p.m. Advance registration is required through the Stratford Recreation Department. Tour size is limited to 25 individuals per time slot.

The Stratford Point Lighthouse is owned by the U.S. Coast Guard, who in 2019 gave Town access to the lighthouse and its surrounding buildings and property provided the Town paid for the care and maintenance. The lighthouse itself is filled with lead contamination and cannot be entered, or viewed from the interior, at this time.

The keeper’s cottage may be accessed and so may the lighthouse grounds. The former Remington Gun Club property, under the management of Audubon Connecticut, is also available to the public during the Open House tours.

Fun Facts and History of the Stratford Point Lighthouse

Stratford Point Light is a historic lighthouse at the mouth of the Housatonic River. The second tower was one of the first prefabricated cylindrical lighthouses in the country and remains active. It sits on a 4-acre tract at the southeastern tip of Stratford Point.

Stratford was an active port in coastal trade, shipbuilding and oystering in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. There was a light at Stratford Point long before a formal lighthouse was built. Tradition holds that in colonial times a bonfire was lit at the point when a boat was expected on a foggy night, and later, wood was kept burning in an iron basket attached to a pole.

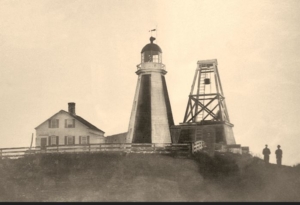

After congress allocated $4,000 on March 3, 1821, four acres of land were purchased on Stratford Point from Betsy Walker, and a twenty-eight-foot wooden octagonal lighthouse was built under the direction of Judson Curtis. Just the third light station erected on Long Island Sound, Stratford Point Lighthouse was established in 1822 and consisted of the octagonal tower, with its sides painted alternately black and white, attached to a one-and-a-half-story keeper’s quarters.

President Thomas Jefferson dedicated the Stratford Point Light.

Autumn of 1822 brought one of the worst gales ever recorded at Stratford Point. Houses blew off their foundations, and hundreds of trees were ripped from the ground. The seas were so high and the winds so strong that salt spray was recorded three-and-a-half miles inland. Miraculously, the new lighthouse withstood it all.

Stratford Point Light has often felt the brunt of storms, and the location is frequently foggy. One keeper had to ring the fog bell for 32 consecutive hours; another rang it in a February storm for 104 hours; then another 103 hours after a brief rest.

In 1911, there was an installation of a compressed-air fog siren. The bell tower was removed during the work and replaced with a brick building used to house the two engines needed to operate the siren’s air compressor. “On foggy nights, the mournful notes of the great horns flinging their penetrating warning far out into the Sound awaken the echoes of the Housatonic River.”

Neighbors did not take kindly to the new fog signal. One woman rang up Keeper Judson and asked him why he wanted to ruin everyone’s nerves. “Well Mrs. Dunbar,” Judson replied, “If that old siren was a noted singer in New York you would be the first one to go hear him and say it was fine. Anyway, I cannot stop it. Maybe if you ring up President Roosevelt he might do something for you. You see he’s got more power than I have.”

A sounding board and reflector were soon erected to focus the sound out over the water as much as possible.

According to The History of Lordship, in 1872 “the buildings of this station are very old and unfit for occupation.” An estimate for a suitable dwelling over which the tower may be placed, was submitted in the last annual report (to the United State Coast Guard). It is recommended that the amount then submitted be appropriated, $15,000.

The Guiding Light

The records of the lighthouse show that there have been a large number of gallant rescues made by keepers of the light at various times of persons who had got into difficulty in craft among the rocks and in the mouth of the Housatonic River to the east of the Point. In 1855 a fifth order lens was added to the 28-foot wooden tower. In 1881, the tower and dwelling were razed and replaced with a 35-foot tall, brick lined cast-iron tower and equipped with a third order Fresnel lens.

With the ever increasing activity in navigation on the Sound and the value mariners placed on Stratford Light, the United States Lighthouse Service decided that it would still further increase the efficiency of the light be superseding the old oil system with electricity, a beam of light that sweeps from Old Stratford Point from a powerful 750 watt electric lamp operated by current derived by transmission wires from shore. By means of powerful prismatic lenses the light is caught up, collected and thrown out in one concentrated ray with an intensity of over 300,000 candlepower. Once every 30 seconds the flash sweeps the sea being visible for many miles, forming a strong reliable light visible in any fog, a light that mariners invariably use as their chief departure beacon in setting their course down the Sound.

Electricity also superseded the old gasoline engine in the operation of the fog horn which sends a three blast warning seawards every 40 seconds Stratford Point Lighthouse lost its lantern room in 1969 to accommodate the installation of automated DCB-224 aerobeacons. These powerful beacons for a time made the light the most powerful on Long Island Sound.

The old lantern was donated to the Stratford Historical Society, and it was displayed at Boothe Memorial Park in Stratford for 21 years.

Coast Guard personnel continued to live at the lighthouse until 1978, after which the station was controlled via microwave radio from Eaton’s Neck on Long Island. The light was automated in 1970 with a modern beacon. It is an active aid to navigation and used for Coast Guard housing. To prevent vandalism, the dwelling was restored and again occupied by the Coast Guard starting in 1982.

In 1990, a smaller optic was installed and the lantern was refurbished and reinstalled at a cost of about $80,000, with a dedication ceremony on July 14, 1990. The tower was repainted in 1996, keeping its distinctive markings of white with a brown band in the middle.

The tower was repainted in 1996, keeping its distinctive markings of white with a brown band in the middle. Today, the unfailing light still guides mariners past the shifting sand bars of the mouth of the Housatonic River.

The lighthouse was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1990.

Head keepers (And Their Assistants)

Lighthouse keepers became civil service employees in 1896. The care of the nation’s lighthouses moved from agency to agency until 1910, when Congress created the Bureau of Lighthouses. The U.S. Coast Guard took over responsibility in 1939.

When researching Stratford Point lighthouse keepers from various sources the following list was found. This list, as well as keeper information, in all probability is incomplete.

Samuel Buddington (1822 – 1843)

Samuel Buddington was hired as the light’s first keeper, and members of the Buddington family continued to watch over Stratford Point for almost fifty years. Samuel Buddington’s maintenance and housekeeping habits apparently left something to be desired, at least according to an 1837 inspection report: “This lighthouse is in the worst order imaginable. The oil was when I visited it dripping from the lantern nearly to the base – the copper of the lantern deck is ripped up in many places, allowing a free passage for the oil form the lamps, under which there are no drippings [tray] to catch it. There are the strongest indications of this lighthouse being kept in the most careless, and slovenly manner.”

William Merwin (1843 – 1844)

Samuel Buddington (1844 – 1848)

Amy Buddington (1848 – 1861)

After Samuel Buddington passed away in 1848, his wife Amy became keeper, and she received the following glowing report in 1850, “Light-house and dwelling, and in fact the whole establishment, is in good order.” Her son Rufus, who became the official keeper in 1861, assisted Amy Buddington.

Rufus Warren Buddington (1861 – 1869) Edward W. Buddington, Assistant, (1866 – 1869)

Rufus and Eliza Buddington raised eight children in the keeper’s cottage, but lost four of them to diphtheria during the winter of 1861 – 1862.

Benedict Lillingston (1869 – 1874); Assistant Frederick Lillingston (1869 – 1874)

“There was no gathering storm in the October night air in 1871 as the steamer Elm City passed Stratford Point Lighthouse. No apparent reason why the light burned unusually dim, but even still, the captain was grateful for that small light warning of the shifting sand bars and strong currents formed where the Housatonic River meets Long Island Sound.

It was many years later, when the Bridgeport Sunday Post interviewed the then grown granddaughter of the keeper of Stratford Point Lighthouse, that the mystery of the dim light was revealed. On that night in 1871, Keeper Benedict Lillingston and his son, Assistant Frederick Lillingston, left the lighthouse to answer the call of a distressed vessel. Twelve-year-old Lottie Lillingston, visiting her grandfather and uncle and left alone at the lighthouse, noticed the light had gone out. There was one thing she was certain off, the importance of the light. She lit a brass safety lamp, then carefully climbed the steps of the tower. Going only by what she had seen her grandfather do, she stopped the clockwork, suspended the safety lamp in the lantern, and then restarted the rotation.”

Assistant Charles Hurst (1874 -1875)

John L. Brush (1874 – 1879), Assistant Abigail W. Brush (1875 – 1879)

March 19, 1879 – John L. Brush, keeper of the Stratford light, has resigned and his resignation has been accepted by the proper officers. The cause is not stated, but perhaps the life was too exciting, dangerously accelerating the action of the heart. We say perhaps! Light housekeeping is not generally perilous. (History of Lordship)

Jerome B. Tuttle (1879 – 1880), Assistant Mary Tuttle (1879 – 1880)

By 1867 the original tower was in disrepair and the keeper’s house was considered too small for a keeper and assistant. The authorities delayed rebuilding by appointing a married couple, Jerome and Mary Tuttle, as keeper and assistant. They were succeeded by another husband and wife, Theodore and Kate Judson. The present cast-iron tower, 35 feet tall, was finally built along with a new keeper’s house in 1881.

Assistant Joshua A. Overton (1898 – 1899),

Theodore Judson (1880 – 1919), Assistant Kate F. Judson (1880 – 1882)

“Theed” Judson was keeper from 1880 to 1921. It was said when Judson retired that he had not had a vacation in 39 years.

Judson once made an extraordinary claim in a local newspaper. He said that he had seen as many as 12 to 15 mermaids frolicking in the waves off the point. In fact, he said he once almost caught one of them, and he managed to salvage her oyster shell hairbrush. “They’re a grand sight,” he said of the mermaids. It is said that Judson’s friends were never able to get him to retract the mermaid tale.

In July 1897, Herman Chase and Edward Howe of Bridgeport were having good luck fishing off Stratford Point while the tide was slack. When the tide turned, the men attempted to raise anchor, but in so doing upset their small boat. Chase valiantly helped Howe, who couldn’t swim, stay afloat, but this extra load made it impossible to reach the upset boat.

Agnes Judson, the keeper’s daughter, gained fame as a swimmer who won competitions in the area. One summer day when she was 17, Agnes watched from the top of the lighthouse as the seas became increasingly rough. Two fishermen about 100 yards offshore were trying to pull up the anchor of their small yawl, and the waves caused both to fall into the sea.

Agnes ran down the lighthouse stairs, rang the fog bell to attract attention, and then swam out to assist them. Keeper Judson and his son Henry were working in a field at the time, but when they heard the fog bell, they rushed to the scene and swam out to the fishermen’s boat. She called to her brother Henry, and both swam out to the fishermen. One of them was about to go under a second time when Agnes got a rope to him in the nick of time. Agnes and Henry managed to pull both of the men safely back to shore and reach the upset boat.

After righting the boat, the Judson’s picked up Agnes and the two men and safely transported them to shore. Agnes refused to accept any gift or recognition for her heroism, and after having dried their clothes, the two fishermen returned to Bridgeport.

When contacted by a reporter, Anges said, “I do not see what makes people try to make such amount of matter of such a little thing. It was of no consequence, and did not amount to much. You will oblige me by saying nothing about it.”

In 1900, Keeper Judson and his son saw two deer wade into the sound near the lighthouse and start to swim. Curious as to where they were headed, Judson launched a boat and followed behind them as far as Stratford Shoal Lighthouse, at which point he was convinced they were intent on swimming the entire thirteen miles to Long Island.

On June 20th, 1911, a little tin can sealed at both ends floated ashore at the Stratford lighthouse and was picked up by Theodore Judson, keeper of the light. On being opened the can was found to contain a scrap of old paper bag on which was written the following: “Ship Mary S. Crayne, London to River Platte, wrecked off Hatteras, February 2d, 1901. Have been on raft ten days. Last bit ate and drank. Please tell mother. James P. O’Reilly. No. 22 St. Catherine Street, Montreal, Canada.”

“December 24, 1912: Captain Herbert Buck, while painting the tower at the Stratford lighthouse, fell from a ladder to the ground, a distance of over 30 feet. Keeper Thene Judson picked up the victim and found him in a dangerous condition. A hurry call brought a physician who found a fractured rib besides the shock of the fall. Captain Thene took in the patient and will care for him at his home. If there are no internal injuries, Captain Buck will be the first man to live after falling from a lighthouse tower. His escape is considered almost miraculous.” History of Lordship

After thirty-four years at Stratford Point, sixty-five-year-old Keeper Judson was informed in 1914 that he was being transferred to a light off Newport, Rhode Island. Officials of various steamboat companies, whose steamers transited the sound, signed a petition protesting the action, and one captain stated that he always felt safe with Judson on the point as not once during his service had the light or fog signal failed. The protestations proved successful, and Judson remained at the station until his retirement in 1919.

Assistant Clarence R. Redfield (1911)

Assistant Henry B. Morris (1911 – at least 1912)

William J. Lavell ( – 1913)

February 20, 1914: LIGHTHOUSE KEEPER ALLEGES FRAME UP: Theodore Judson, keeper of Stratford Point Lighthouse, who was ordered to take charge of an offshore light at Newport, Rhode Island, declared today that he was a victim of a frame up. Judson has been the keeper of the Stratford Point Light for thirty-four years. Recently he has had trouble with his assistant, William Lavelle who preferred charges against his superior a short time ago. The charges were returned after an investigation with the statement that here was little or no foundation for them. Judson filed counter charges against Lavelle.

Assistant William F. Petzolt (1913 – 1919)

For about 30 years Captain Judson maintained the light without an assistant except what he received from his wife, a son, and his two daughters. In 1913 he was allowed an assistant. William Petzolt, who succeeded him to the care of the light. Petzolt was from Stamford, and for a number of years had charge of the Governor’s Island light in New York harbor.

William F. Petzolt (1919 – 1946), Assistant James A. Kirkwood (1928 – 1946)

JUNE 10, 1925 – Lightkeeper Pitzolt, after experiencing nearly as many varieties of weather and temperature in a fortnight as the proverbial “57” ranging from nearly 100 in the shade, through hail and thunderstorms to 10 degrees above freezing, Lordship and the adjacent coastline settled down for the night to a dense fog at ten o’clock Monday evening, when Lightkeeper Pitzolt started the fog horn engine at Stratford Point. In the absence of Assistant Lightkeeper Dean, who is a away with Mrs. Dean on a two days trip to Hartford, Mr. Pitzolt must do relief-duty as well, which means a continuous vigil without delay until his assistant’s return.

Head Keeper Petzolt and Second Keeper James Kirkwood are on duty day and night. During the long hours between dusk and dawn there is much to be done in watching the light, keeping the mechanism that operates the revolving apparatus wound up, holding in readiness for immediate use the auxiliary oil burners that are installed in the lantern room in case the electricity fails. For it is the creed and motto of every member of Uncle Sams Lighthouse service that the light must never go out. (History of Lordship)

Assistant George H. Tooker (1919 – at least 1920)

Assistant Phillips A. Channell (at least 1921)

Assistant Arthur G. Reuter (at least 1922)

Assistant Harry B. Dean (at least 1925)

Daniel F. McCoart (1946 – 1963), Assistant William A. Shackley (1946 – at least 1962)

Daniel F. McCoart, a Providence native, Navy veteran and former light heavyweight boxer, was the civilian keeper from 1945 to 1963. He lived at the lighthouse with his family. William Shackley was the assistant keeper for many years, and he also lived in the keeper’s house with his family. Keeper McCoart retired in 1963 after 44 years in the Lighthouse Service.

Coast Guard Engineman 1st Class Richard Fox (1963 – 1967)

The Coast Guard gave up lighthouse keeping on January 19th, 1967