In 2019, my husband Adrian and I stepped out of a rental car in front of a midcentury summer house, weather-beaten, and framed by two aging pines. In front of the house, two exhausted septuagenarians. We were confused, too. The realtor was nowhere. The soon-to-be former owners were not expected. Now a small Black woman with round glasses was asking me to look after the plants she could not fit into the moving truck.

Adrian and I were nodding anxiously when the realtor appeared. The moving truck growled to life, and the couple made slow moves toward their car.

“Wait!” shouted the realtor, some early spring air catching her coiffed blond hair. She corralled the four of us into a vignette: the old owners and the new, wearing the roofline of the house like a hat.

Afterwards, the couple drove off into a new life and we went inside to begin ours.

March 2025. A silver sedan pulls up our driveway about fifteen minutes past eleven in the morning. As she steps out, Lynne leans her frame backward to catch sight of the house’s roofline. Her husband Tom grins through gray stubble.

“People don’t do this!” Lynne shouts toward the reaching arms of an old silver maple. She’s laughing now, about families, about homeowners, about sharing. I open the front door to my house; to the house Lynne’s parents built about 1955.

A house with a history that almost never was.

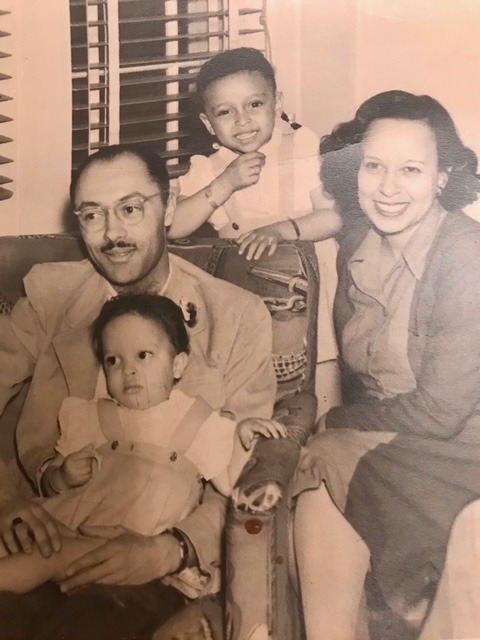

Dr. Frank Elliott, Lynne’s father, came to the Stratford area from Virginia, with his wife Edith and fledgling family in 1945, where they immediately “dedicated themselves to helping others.” [1] World War II had ended, and soon Frank had eyes on a peaceful parcel in Lordship, a stone’s throw from the historic lighthouse, where his family could grow.

No, said the developer. Frank could not purchase the parcel, because he was Black.

Historically, rigging real-estate markets with restrictions to exclude minorities is referred to as the practice of “red lining.” These racist real-estate schemes were common in the twentieth century, and are still in existence today. Frank found another way.

He asked his lawyer’s wife, a white woman from nearby Monroe, to purchase the plot and deed it back, so the Elliotts could build a house along the Sound, just as their white neighbors had, no matter what any contract said. In 1952, the developer sold the parcel to one Helen Maliszewska, who in turn sold it to Edith B. Elliott, the wife of Dr. Elliott [2], a woman of Jewish, Black and Irish descent.

This was not the last struggle the Elliotts would face in Lordship.

March 2025. In the living room, Lynne’s face twists. “You got rid of the bookshelves?”

“Yes,” I say, apology syruping my voice. “They were getting a bit tired. We replaced them with something midcentury to suit the house, see?”

She nods at the teak, warmed by morning sun coming in through the back windows.

“Do you know about the passive solar?” Tom asks. He’s appeared beside me, an easiness about his shoulders. He’s gazing out the windows.

“Tell me what you know?” I say.

“Well, the soffit there…that’s designed to catch the sun in winter and pour it back into the living room to keep it warm…”

Throughout the early 1950s, the modern frame of the Elliot house took shape: a low-slung Frank Lloyd Wright inspired bungalow with large windows looking out to the water. Jimmy Cooper, a local man from Bridgeport, built the rip-rap wall and stairs down to the beach. Real estate in the area at the time focused on modest, developer-built cubes, with names like Lordship Shores that advertised “maximum living for the middle income family.” [3]

Folks got curious about what the Elliotts had going on.

In a series of phone interviews in 2024, Frank’s daughters remembered those early years in the 1950s—when cars would slowly snake around the horseshoe driveway, neighbors straining to get a look at the family inside. One night, while the Elliotts were away, all the topsoil was dug up from the yard.

No perpetrators were found.

Lynne recalls “[My parents] were moving into a neighborhood where there were no other blacks. My mother’s attitude always was, “I’m not going into their house and I don’t want them in mine.” And she kind of kept it. We were pleasant and spoke, but that was it.”

Francine, the Elliott’s youngest, was five when the family moved into the house in Lordship. She remembers “my whole childhood, riding my bike up to the drug store and to the hamburger place overlooking the airport, Maraczi’s.” She attended the Great Neck School on Lighthouse Avenue, and also remembers the boy who would not hold her hand in a square dance because of the color of her skin.

Alice, the second oldest, was nine when the family moved in, and used to charge up the bluff by the lighthouse, singing “La Marseillaise.” Later, her theatricality translated to working summers at the Shakespeare Theatre, opened in 1955 on Elm Street. She was almost fired one summer by a feisty Katherine Hepburn, but survived the tiff. Alice went on to direct her own review at the theatre, lauded by actor Morris Karnofsky.

Lynne, the oldest, remembers the cookouts, weddings and celebrities at the house.

“My parents used to give a big 4th of July picnic. We grew up with Jackie Robinson’s kids and Jackie Robinson, and Rachel. They would come down on the 4th of July for the picnic.”

Another time, “these huge black limousines turned into the driveway. And on one side, there was an American flag, and on the other part there was the flag of… God, I believe it was Ghanaian. It was somebody. It was a friend of [my parents]…the ambassador from Ghana to the UN. He came up to spend the weekend at the house.”

By the 1970s, Dr. Elliott was engaged as the founder and director of the first freestanding methadone clinic in Bridgeport, where he “not only developed the program, but also initiated an active peer counseling program as well as an ongoing educational component for all clinic participants.” [4] The program was hailed in 1972 as “an oasis of hope” [5]

Edith B. Elliott passed away in 1996, celebrated as a “city activist and humanitarian,” for her work in nearby Bridgeport with the NAACP, Jack and Jill Inc. (that assisted children), and Fairfield County Chapter of Girls Friends, among others. The church the Elliotts attended, St. Mark’s Episcopal, was too small for so big a life celebration, so they threw open the doors to Christ Episcopal Church on Main Street, in Stratford. [6]

Dr. Elliott passed in 2006, a physician for sixty years, who left a lasting legacy through community care and the civic work he did with the Governor’s Task Force on Drug Addiction, Family Service Society of Bridgeport, and the Rotary Club, among others. [7] The day after he passed, Lynne remembers, one of the old maples in the center of the horseshoe driveway came crashing down.

March 2025. “You kept it!” Lynne exclaims from somewhere in the dining room before I can answer. She points to the wooden pendant lamp above the table. This is the miraculous call of the day. Everyone else wanted to knock the house down. You kept it. We kept it.

The Elliott house, now called lordship house, is a private house with public programs, including funded artists Fellowships.

Editor’s Note: All photos were provided by the author, Michael Todd Cohen, and provided by the Elliott Family with their approval.

Sources:

[1] Connecticut Post, Oct 27, 1996.

[2] Land Records of the Town of Stratford.

[3] Bridgeport Post, Aug 19, 1951.

[4] Connecticut Post, Jan 19, 2006.

[5] Connecticut Post, Jan 11, 1972.

[6] Connecticut Post, Oct 27, 1996.

[7] Connecticut Post, Jan 19, 2006.