Get to Know These 20 Common Types of Native Plants

Whether you’re looking to increase your awareness outdoors or attract more birds to your home, let this primer be your guide.

By Carlyn Kranking, Reporter

Audubon Magazine

Plants are absolutely crucial to avian life. Trees, flowers, shrubs, and grasses can serve as shelter, nesting material, and veritable buffets for birds. But not all plants are equal depending where you live: Research has shown that native plants that have evolved within certain ecosystems do a much better job of supporting bird species than non-native ones. Knowing which plants are native and which are not, however, isn’t always easy. This primer should help.

Having a basic level of native plant literacy is beneficial for a variety of reasons. When out in the wild, it can make you a better birder, since these are the plants that birds are more likely to interact with in their natural habitats. Plus, knowing what plants are best suited to your region will help make your yard, balcony, or patio more bird friendly. With a little work and planning, you could be rewarded with an iridescent Ruby-throated Hummingbird drinking from tubular columbine, or a group of Cedar Waxwings nibbling on serviceberries.

Understanding the important role native plants play will also make you better equipped to be a voice for your community, says Marlene Pantin, partnerships manager for Audubon’s Plants for Birds program. “If we want to be having conversations with city officials, we have to come with plants in mind that are best for them to use on city streets,” she says.

The groups listed here are some of the most common native plant genera in the country. In the Lower 48 states in particular, you’re likely to find species under many of these umbrellas that are native to your region. But non-native species in most of these groups might also be available—that’s why it’s important to know what’s recommended for your locality. Once you find your favorites from this list, just check out Audubon’s native plants database to find which species are recommended for your zip code.

Trees

Oaks (Quercus spp.)

Wilson’s Warbler on Bur Oak. Photo: OHFalcon72/Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Identifiable by their deeply ridged bark and lobed leaves, oak trees bring colorful fall foliage to your yard, street, or nearby park. Height differs by species, but many of these often slow-growing trees can reach 40 to 80 feet tall. They’re a hub for biodiversity, supporting countless birds and insects—including caterpillars of 557 species of butterflies and moths.

Plant Notes: There are upwards of 200 oak species native to the United States, according to the Biota of North America Program. Find your local native species on the Audubon native plants database.

Bird Notes: All sorts of songbirds will eat insects that live in oak trees, while woodpeckers, jays, and others will eat the acorns. Oak trees also make great homes for birds that nest in cavities, such as woodpeckers, bluebirds, Barn Owls, and Wood Ducks.

Pines (Pinus spp.)

Red Crossbill on Ponderosa pine. Photo: Evan Barrientos/Audubon Rockies

While most people are familiar with pine trees, they might not be aware that there are about 120 species of this conifer worldwide. These evergreen trees have pointed needle leaves that help store water and provide year-long canopy cover that shelters animals.

You can distinguish a pine from other cone-producing trees by its clusters of needles in groups of two, three, or five. Pines support 203 butterfly and moth species, and their seeds tucked away in cones are a favorite snack for birds.

Plant Notes: In the East and Upper Midwest, select an eastern white pine (P. strobus), which hosts almost 50 species of birds. In the West, try a Ponderosa pine (P. ponderosa), western white pine (P. monticola), or sugar pine (P. lambertiana). Bristlecone pines (P. aristata and P. longaeva) are native to the Southern Rocky Mountain area, and in the South, try a longleaf (P. palustris) or loblolly (P. taeda) pine. Avoid non-native pine species such as the Scotch Pine (P. sylvestris) and Australian Pine (P. nigra).

Bird Notes: Finches, nuthatches, grosbeaks, and chickadees will eat pine “nuts”—the seeds from the pinecones—and birds can find shelter under the leafy limbs. Pine needles are good material for making nests.

Dogwoods (Cornus spp.)

Pacific dogwood. Photo: Maggie Starbard

The characteristic white or pink blossoms of a dogwood tree are actually not petals but leaves (called bracts) surrounding small green flowers. Nevertheless, they’re a beautiful springtime sight. Throughout the year, a dogwood’s display continues as its oval-shaped leaves turn red in the fall and red fruit appears from fall into winter, though some species produce white or blue-black fruit. Come winter, dogwood trees’ scaly bark, often compared to alligator skin, stands out among bare branches. Dogwoods benefit the ecosystem by pulling calcium from the ground up into their leaves and enriching the soil when they fall.

Plant Notes: There are about a dozen species of dogwoods native in the United States. In the East and Midwest, try the flowering dogwood (C. florida). Westerners, look for the Pacific dogwood (C. nuttallii), which produces a bonus burst of color in the fall, when it may bloom a second time.

Bird Notes: More than 35 species of birds will eat the berry-like fruit (called a drupe) produced by dogwood trees. These include Northern Cardinals, Tufted Titmice, Dark-eyed Juncos, Gray Catbirds, bluebirds, and waxwings.

Willows (Salix spp.)

Willow Flycatcher on willow. Photo: Kelly Colgan Azar/Flickr (CC BY-ND 2.0)

Willows are quite flood-tolerant and prefer to grow in slightly wet soil. Many species have petal-less, long flowers called catkins, and each flower is male or female—some species, such as the pussy willow, have entire trees that are male or female.

Plant Notes: Arguably the most famous willow, the Weeping Willow is actually a non-native species. But never fear, it has lovely native alternatives such as the fast-growing black willow (S. nigra), native in the Eastern and Central U.S., and the pussy willow (S. discolor), which grows in the northern and eastern parts of the country. If you place a willow branch in water, it can sprout roots and get transplanted outside.

Bird Notes: Migratory birds like kinglets and warblers can feed on insects that willow blossoms attract, and insectivorous birds, woodpeckers, and the Yellow-bellied Sapsucker are also attracted to black willow trees. Hummingbirds and others make nests using the fluff from pussy willow catkins.

Flowers

Milkweeds (Asclepias spp.)

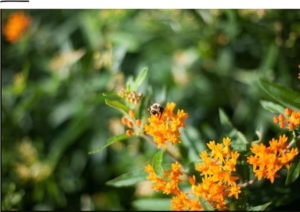

Butterfly weed. Photo: Kristina Deckert/Audubon

Milkweeds grow ball-shaped clusters of flowers that can be purple, pink, red, white, green, yellow, or orange. In late summer, narrow green seed pods adorn these plants. Milkweed famously attracts monarch butterflies and provides food for their caterpillars. As monarch caterpillars eat milkweed, they develop a toxicity that makes them undesirable to predators as an adult. But milkweeds are also useful for birds, particularly as nesting materials.

Plant Notes: You want to avoid tropical milkweed—this is non-native, and it doesn’t die back in the winter, like most milkweed. This means two things: Monarchs might be tempted to stay on this plant in winter rather than migrate, and a milkweed-dwelling parasite that kills monarchs can also stick around all year long. Instead, depending on your region, choose a native variety such as common, swamp, purple, white, or whorled milkweed, or butterfly weed, which is the most drought-tolerant milkweed.

Bird Notes: Some birds, like orioles and finches, use fibers from fluffy milkweed seeds to line their nests. Hummingbirds like to feed on milkweed. And insect-eating birds such as Indigo Buntings may be attracted to the caterpillars that milkweed supports.

Coneflowers (Echinacea spp.)

Purple coneflower. Photo: Kristina Deckert/Audubon

Coneflowers have a raised center with petals forming a flat ring around it. This genus, called Echinacea, is named for the Latin echino, meaning spiny, as its center looks rather pointy. The blossoms top leafy stems that stretch 2 to 4 feet tall in sunny areas with well-drained soil. Pollinators, especially bees, love these flowers.

Plant Notes: Look for the pale purple coneflower (E. pallida) in the Central U.S., and the purple coneflower (E. purpurea) in the Southeast. Check the native plants database for other local species.

Bird Notes: Insectivorous birds are drawn to these pollinator magnets while they’re in bloom in summer and early fall, and hummingbirds will sip coneflower nectar. Goldfinches, Blue Jays, Northern Cardinals, and other species like to eat coneflower seeds in the fall and winter.

Coneflowers (Rudbeckia spp.)

Black-eyed Susan. Photo: Camilla Cerea/Audubon

Rudbeckia is another genus of coneflower, which is native to prairies and damp woodlands. One common Rudbeckia coneflower species is the Black-eyed Susan (R. hirta), identifiable by its yellow-orange halo of petals around a dark center.

Plant Notes: Black-eyed Susans are common in native plant gardens, as they can attract 17 kinds of butterflies and moths. With a couple dozen Rudbeckia species native to the U.S., be sure to use the native plants database to find your local variety.

Bird Notes: A wide range of species like to eat the seeds of Rudbeckia flowers, including Northern Cardinals, goldfinches, chickadees, nuthatches, and sparrows.

Sunflowers (Helianthus spp.)

Common sunflower. Photo: Tania C. Parra/Forest Service

These golden blossoms are known for their height—many grow taller than the average person. But with dozens of species native to North America, there’s plenty of variety: The little sunflower (H. pumilus), for example, averages just 1 to 3 feet tall. Each sunflower is actually made up of scores to thousands of smaller blossoms—in fact, a sunflower’s center consists of many tiny blooms, and each petal is also classified as a flower of its own. It’s no wonder pollinators love these plants.

Plant Notes: Check to find out which species are best for your area. Some species, such as the common sunflower (H. annuus), are native in some parts of the country but invasive in others.

Bird Notes: A wide variety of species like to eat sunflower seeds, including Northern Cardinals, goldfinches, siskins, grosbeaks, jays, finches, and many others.

Sages (Salvia spp.)

Autumn Sage. Photo: Paul Ratje

Maybe you’ve used sage in recipes to add its earthy flavor or nutritious benefits, like antioxidants and the healing Vitamin K. Or maybe you’ve burned dried sage leaves, which can purify the air, remove bacteria, and repel insects. Pollinators like to use sage, too—these fast-growing and drought-tolerant flowering plants attract hummingbirds, bees, and butterflies.

Plant Notes: In the Central and Southeastern U.S., try pitcher sage (S. azurea). Many sage species are native to the Western U.S., especially in Texas. Use the Audubon native plant search tool to find what species are best at your location.

Bird Notes: When a hummingbird sticks its beak into a sage flower, it pushes a kind of “lever” that releases the pollen-containing stamen, which is usually hidden in a sage’s petals. The pollen then rubs onto the hummingbird’s head and travels to the next blossom.

Blazing star (Liatris spp.)

Dotted blazing star. Photo: Evan Barrientos/Audubon Rockies

This plant grows 2-5 feet tall and can be recognized by its flowers on a stalk, which bloom from the top down. It has an underground stem called a corm, which looks like a bulb and stores water to help the plant through dry times. Blazing star grows best in full sun with poor, rocky soil and dry conditions.

Plant Notes: In the eastern U.S., look for rough blazing star (L. aspera) or gayfeather (L. spicata). In the West, choose Rocky Mountain blazing star (L. ligustylis). For residents of the central U.S., try prairie blazing star (L. pycnostachya).

Bird Notes: The seeds of blazing star may attract American Goldfinches, Black-capped Chickadees, Indigo Buntings, or Tufted Titmice, and insectivorous birds may eat the butterflies and other insects that like this plant.

Columbines (Aquilegia spp.)

Eastern red columbine. Photo: Justin Merriman

The columbine flower is named after not one, but two birds—columbine comes from the Latin word columba, or dove-like, and its scientific name, genus Aquilegia, is related to the Latin word for eagle: aquilae. Supposedly, the upside-down flower looks like a cluster of doves, and its petals stretch backward into tubes called spurs, which resemble an eagle’s talons. But that doesn’t scare away the pollinators that frequent this slight shade- and sun-loving plant.

Plant Notes: Easterners, choose the eastern red columbine (A. canadensis). In the West, find your local variety of blue, yellow, or red columbine.

Bird Notes: In spring and summer, shimmering hummingbirds drink nectar from narrow columbine flowers.

Goldenrods (Solidago spp.)

Goldenrod. Photo: Evan Barrientos/Audubon Rockies

Goldenrods are magnets for pollinators; they support 115 different butterfly and moth species, according to native plants researcher Doug Tallamy. True to its name, this plant has stalks of yellow flowers. Goldenrods bloom from the end of summer into the fall, which makes them a good plant for a butterfly garden and to complement the summer-blooming milkweed.

Plant Notes: Most goldenrod species are native to North America, and many are native to the eastern U.S. Find what’s best for your area with the native plants database.

Bird Notes: Woodpeckers and chickadees might eat fly larvae that live on goldenrods, and other insectivorous birds may be drawn to the butterflies. Plenty of birds also eat goldenrod seeds, particularly the American Goldfinch.

Asters (Symphyotrichum)

Purple aster. Photo: Parker Seibold

Asters attract up to 112 species of butterflies and moths, making them, like goldenrods, a worthy addition to a fall-blooming butterfly garden. Their narrow petals can be purple, pink, blue, or white. Aster species vary in height, but many grow between 1 and 3 feet tall. They’re also versatile—some species are sun-loving and others thrive in shade.

Plant Notes: In the central and eastern U.S., try the aromatic aster (S. oblongifolius) or New England aster (S. novae-angliae). Out West, look for the western aster (S. ascendens) or the rayless aster (S. ciliatum).

Bird Notes: Asters might attract insect- and seed-eating birds, especially during fall migration, when they bloom. Look out for goldfinches and chickadees around these plants.

Beardtongue (Penstemon spp.)

Beardtongue. Photo: Evan Barrientos/Audubon Rockies

There’s great variety among penstemon species—some are only inches tall, while others stretch feet into the air. Their tubular flowers may be white, yellow, blue, purple, or red. These can be fairly hardy plants, as they appreciate well-drained soil while also being able to withstand dry conditions. Penstemons might be relatively short-lived (three to four years), but they propagate easily and attract butterflies and bees.

Plant Notes: There are about 250 species of penstemons that are native to North America, with many growing in the western United States. Due to the variety of penstemons, check to see which kinds are native to your region using the Audubon native plants database.

Bird Notes: Hummingbirds love to drink nectar from these flowers, and ground-feeding songbirds such as sparrows eat penstemon seeds.

Berries

Serviceberries (Amelanchier spp.)

Serviceberries. Photo: Maggie Starbard

These trees make white flowers in the spring and host bright-colored leaves come fall. Serviceberry leaves support hungry caterpillars, and the flowers attract adult butterflies. The berries themselves are very attractive to birds, but they also taste great to humans—like a blueberry, but sweeter!

Plant Notes: There are many varieties of serviceberry that are native across much of the country. Use the Audubon native plants database to find out what is best for your region.

Bird Notes: Northern Cardinals, Cedar Waxwings, tanagers, grosbeaks, vireos, robins, and other birds are attracted to the fruit of serviceberries. These trees also provide a good nesting spot.

Elderberries (Sambucus spp.)

Rose-breasted Grosbeak on Red Elderberry. Photo: Shirley Donald/Audubon Photography Awards

These trees or small shrubs typically grow 5 to 12 feet tall and support various caterpillars, including that of the largest moth in North America, the cecropia moth. If you’ve seen an elderberry supplement at the pharmacy, that’s because some suggest the dark purple berries may have health benefits for humans, as they’re rich in Vitamin C, fiber, and antioxidants, but the research is inconclusive. (Don’t eat raw elderberries though, as they’re toxic to people—but delicious to birds!)

Plant Notes: American Black Elderberry (S. canadensis) grows in almost all of the Lower 48 states.

Bird Notes: Brown Thrashers, Red-eyed Vireos, Gray Catbirds, warblers, tanagers, orioles, mockingbirds, and waxwings enjoy elderberries.

Blueberries & Sparkleberries (Vaccinium spp.)

Blueberries. Photo: Jeff Blake

All berries in the genus Vaccinium are edible to humans, and these include familiar fruits like blueberries, cranberries, huckleberries, and lingonberries. Another variety is sparkleberry (also called farkleberry), which makes bright red leaves in fall. Blueberries, too, are native to areas of the U.S., and the world’s largest producer of wild blueberries is the state of Maine.

Plant Notes: Try sparkleberry (V. arboreum) in the southeastern U.S., from parts of Virginia and southern Illinois to eastern Texas and south-central Florida. Blueberries grow in the eastern U.S. and Pacific Northwest.

Bird Notes: Songbirds, including Tufted Titmice, robins, thrashers, and mockingbirds will eat sparkleberries, and Bobwhite Quail will browse the berries, too. Blueberries also attract a variety of songbirds, and some might even make their nest in the bush.

Vines & Grass

Honeysuckles (Lonicera spp.)

Trumpet honeysuckle. Photo: Kristina Deckert/Audubon

Honeysuckles like well-drained soil and don’t require a lot of care to grow. Wild honeysuckle may be found climbing trees in forests. These plants add a dash of color to any garden or street with vibrant springtime blossoms and berries in the fall. And of course, you can get a sweet snack by tasting honeysuckle nectar from inside the flowers.

Plant Notes: The non-native species are invasive, so avoid: Amur (L. maackii), Tatarian (L. tatarica), Morrow’s (L. morrowii), and Japanese honeysuckle (L. japonica). All four can be identified by their hollow stems. Non-native honeysuckle can have negative impacts on birds, from being less nutritious than native varieties, to causing higher mortality rates in nests, likely due to less shelter from leaves, increasing predation. Instead, choose a native species such as trumpet (L. sempervirens) or yellow honeysuckle (L. flava).

Bird Notes: Hummingbirds are attracted to the blossoms, and Purple Finches and Hermit Thrushes like to eat the berries in fall and winter. Baltimore Orioles eat the flowers during migration.

Switchgrass (Panicum spp.)

Switchgrass. Photo: Elizabeth Fraser/Arlington National Cemetery

There are more than 400 species of switchgrass, but not all are native to the United States. It’s a prairie grass whose native range extends across the U.S. east of the Rockies. With plenty of sunlight, these grasses grow very easily, requiring little maintenance. This 2.5- to 5-foot-tall plant blooms in the summer and seeds in fall and winter.

Plant Notes: There are some non-native species in this genus, such as the introduced torpedo grass (P. repens), which is displacing native marshes in Florida. P. virgatum is a common native species. Be sure to check which varieties are native to your zip code using the Audubon native plants database.

Bird Notes: Songbirds like to eat the seeds of switchgrass, and the tall vegetation provides shelter for birds.

Muhly grass (Muhlenbergia spp.)

Muhly grass. Photo: Richard Skoonberg/Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Muhly grass is hardy—it’s drought- and salt-tolerant—and it likes sandy or rocky well-drained soils. In late summer and fall, some varieties of these plants display fluffy plumes of color at the tops of the grasses in pink, purple, or white. Come November, the color fades as beige seeds take its place, creating a buffet for many songbirds.

Plant Notes: This grass is native to the central and eastern U.S., from Kansas to Texas to the Atlantic.

Bird Notes: Muhly grass seeds appeal to sparrows and finches, and some birds may use dead stems of this plant in nesting material.