Poetry Lounge

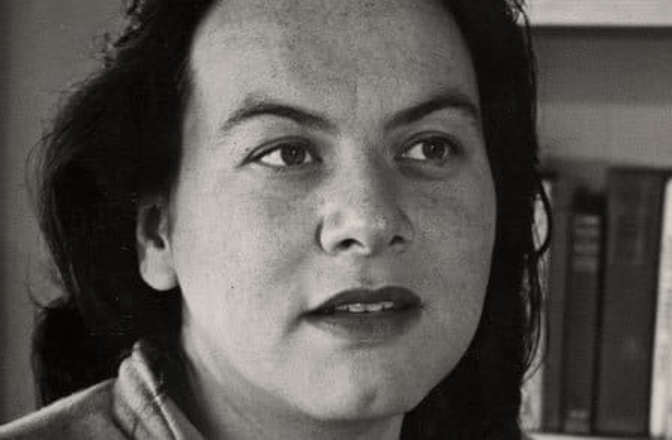

“I hold to the streams below the streams,” wrote the poet Muriel Rukeyser (1913-1980) in her influential The Life of Poetry. Living, as we do, in the riverlands, I think of this statement often. How it points to the unseen and invisible, the vast currents of energy (both natural and manmade) that run beneath our feet at any given moment. A power subterranean, perhaps terrifying in its hidden workings, but one that also connects us all. The streams below the streams could be literal, geological facts (as in the uncanny YouTube video I saw recently featuring “urban explorers” navigating the aquifer that ran beneath the length of an entire local city), but I also interpret this claim to mean the force that gathers and connects us all: language.

In her renown short poem Islands, Rukeyser demonstrates, with an almost frustrated starkness, this notion of a connecting undercurrent (we might call it our unconscious):

Islands

O for God’s sake

they are connected

underneath.

Aside from being an excellent poem to memorize and impress your cohort, this short poem–only eight words–illustrates how even under a given concept like islands, that we so often associate with isolation (the word isolation derives from Latin insula or island) there remains connection, however deep down. In our current times of political division and alienation, I look to Rukeyser’s submerged gaze. Her poems dive down to the common seafloor of what allows us to communicate. Rukeyser reminds us that, as a part of this shared world, we sink and swim together.

Rukeyser was also a keen poet of witness, documentation, and reportage. Her influential Book of the Dead assiduously documents the Hawk’s Nest Tunnel disaster of 1931 in Gauley Bridge, West Virginia. She names names and cites facts, all while attending to the emotional and spiritual realities that accompany the disaster. As a poet and person who feels like every day a new catastrophe is slowly unfolding before our eyes, I see in Rukeyser an example of how to document injustice on the surface while still “holding to the streams below streams.”

One poem that offers me the necessary oxygen to breathe in those currents is her Poem (I lived in the first century of world wars). What most strikes me about this poem (published in 1968) is how contemporary it feels, with its references to being disconnected, with various devices trying to bridge the gap, with global conflict further divvying up the worlds’ hearts and souls. But also the very real hope that these threads that connect us always, will allow us, “To construct peace, to make love, to reconcile/ Waking with sleeping, ourselves with each other,/ Ourselves with ourselves.”

I invite you to read the poem in its entirety (below) and to consider what it means to “reach beyond ourselves,” to reach the profound truth of what it means to be islands connected underneath vast—but not uncrossable—distances.

Poem (I lived in the first century of world wars)

I lived in the first century of world wars.

Most mornings I would be more or less insane,

The newspapers would arrive with their careless stories,

The news would pour out of various devices

Interrupted by attempts to sell products to the unseen.

I would call my friends on other devices;

They would be more or less mad for similar reasons.

Slowly I would get to pen and paper,

Make my poems for others unseen and unborn.

In the day I would be reminded of those men and women,

Brave, setting up signals across vast distances,

Considering a nameless way of living, of almost unimagined values.

As the lights darkened, as the lights of night brightened,

We would try to imagine them, try to find each other,

To construct peace, to make love, to reconcile

Waking with sleeping, ourselves with each other,

Ourselves with ourselves. We would try by any means

To reach the limits of ourselves, to reach beyond ourselves,

To let go the means, to wake.

I lived in the first century of these wars.

(Poems & Image courtesy of PoetryFoundation.org)